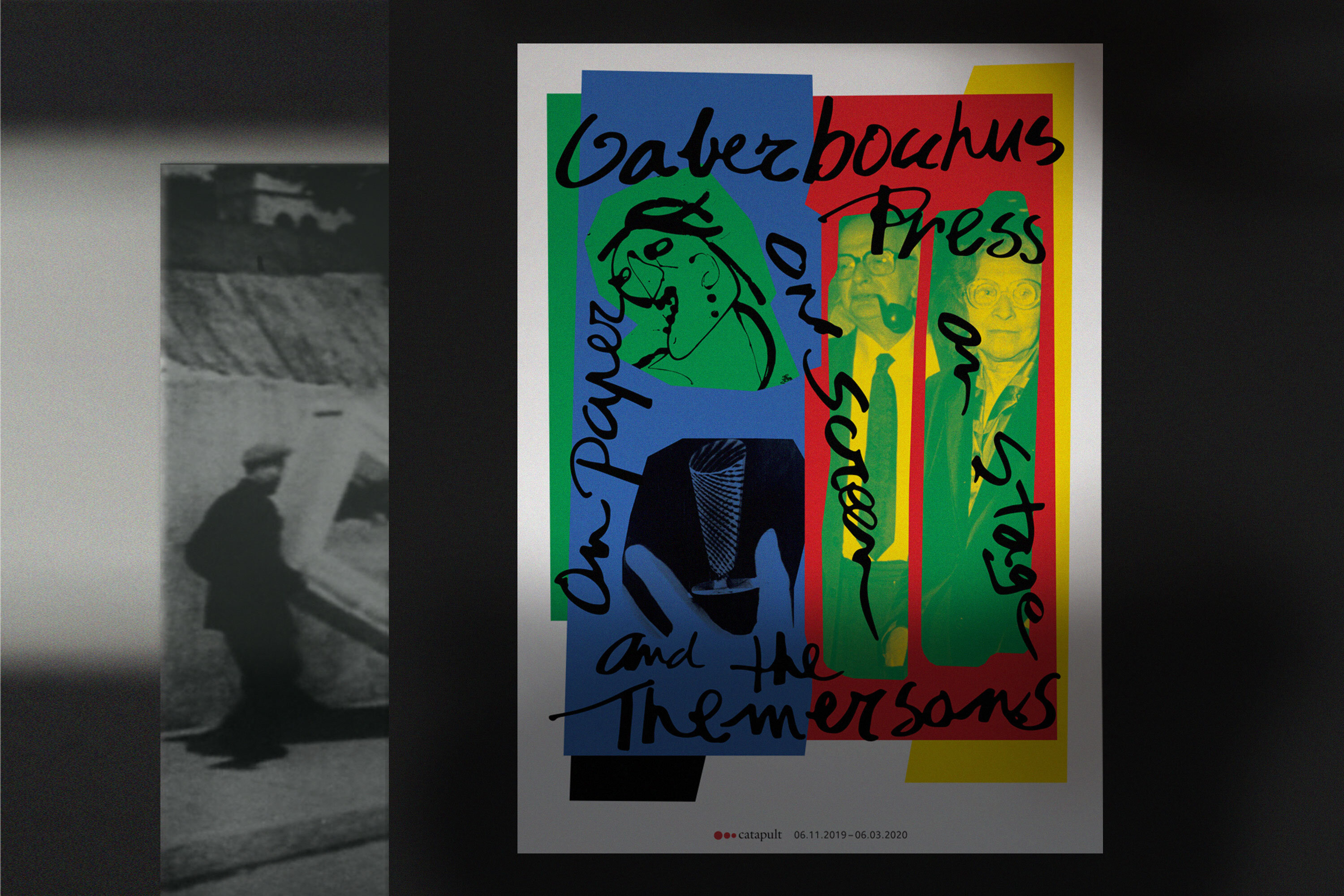

‘Gaberbocchus Press (1948–1979) and the Themersons on paper, on screen, on stage’

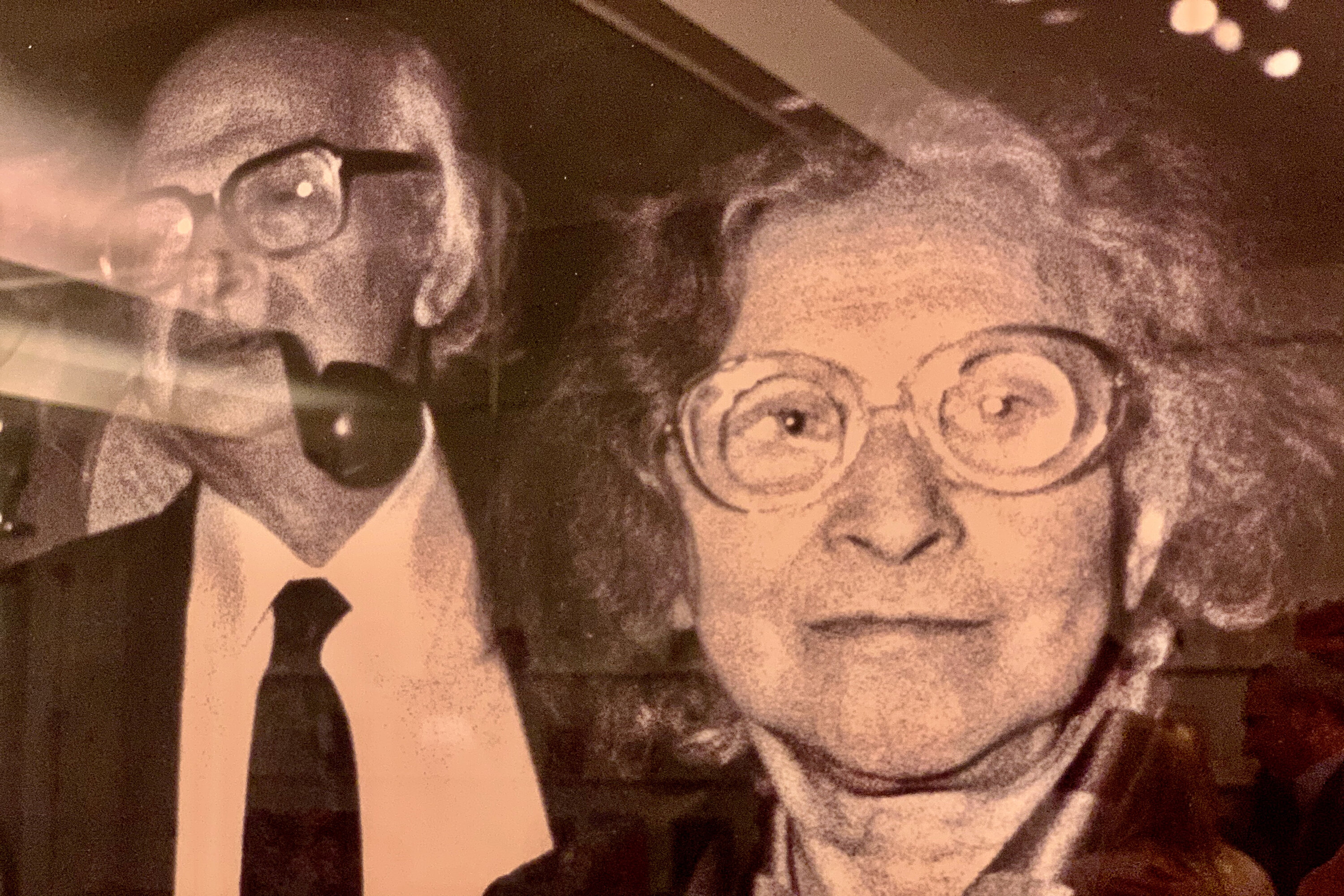

This is the first exhibition in Belgium of the work of the

Polish-English artist couple Stefan (1910–1988) and Franciszka

(1907–1988) Themerson. He was a writer and philosopher, she was a visual

artist and a theatre designer. Together they published and illustrated

books and made experimental short films.

In short: The Themersons on paper, on screen, on stage.

Exhibition 06.11.2019 – 06.03.2020

Catapult, Rubenslei 10, 2018 Antwerp

Hours: Monday–Friday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

(weekends and holidays by appointment only)

Entrance: Free

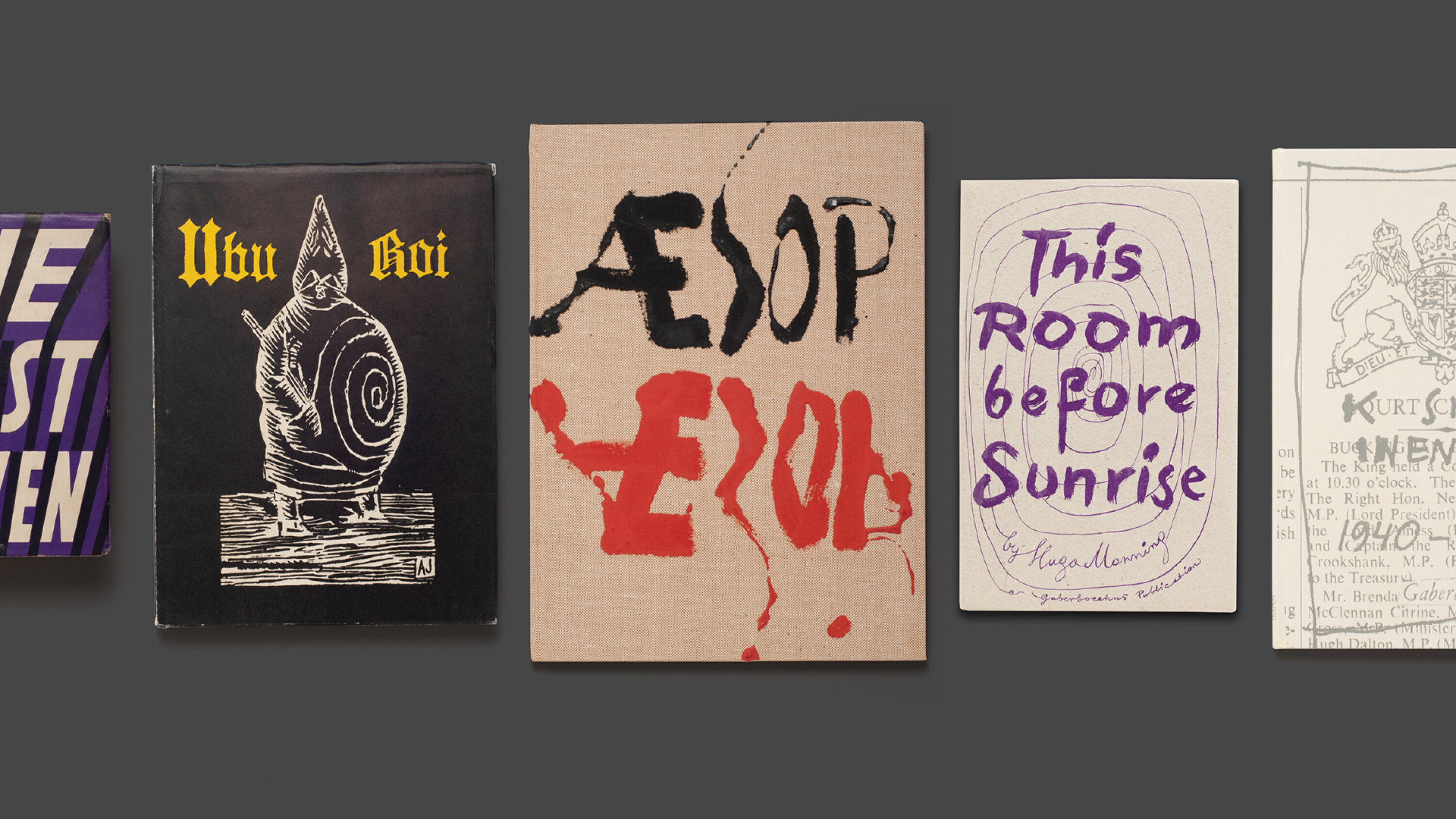

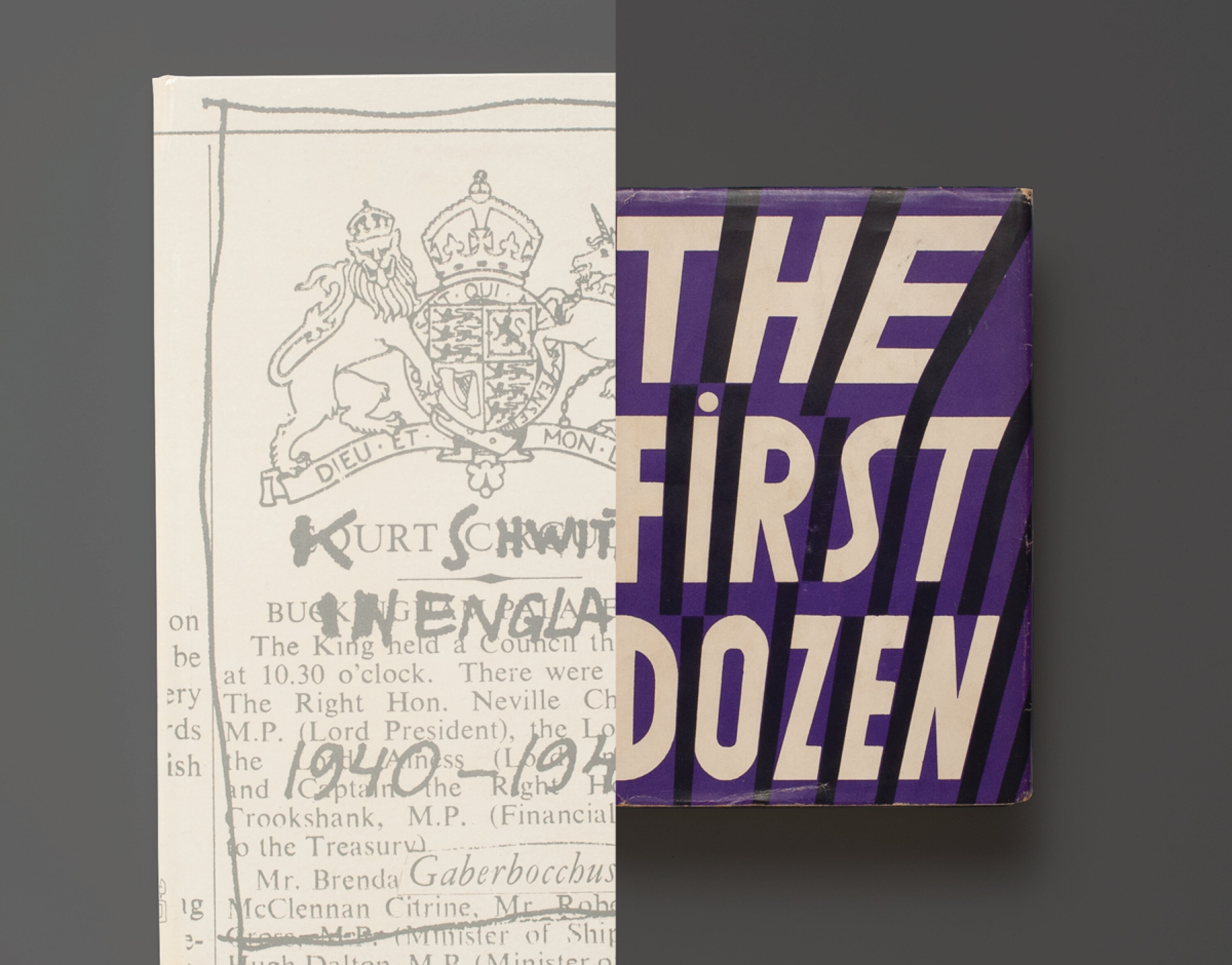

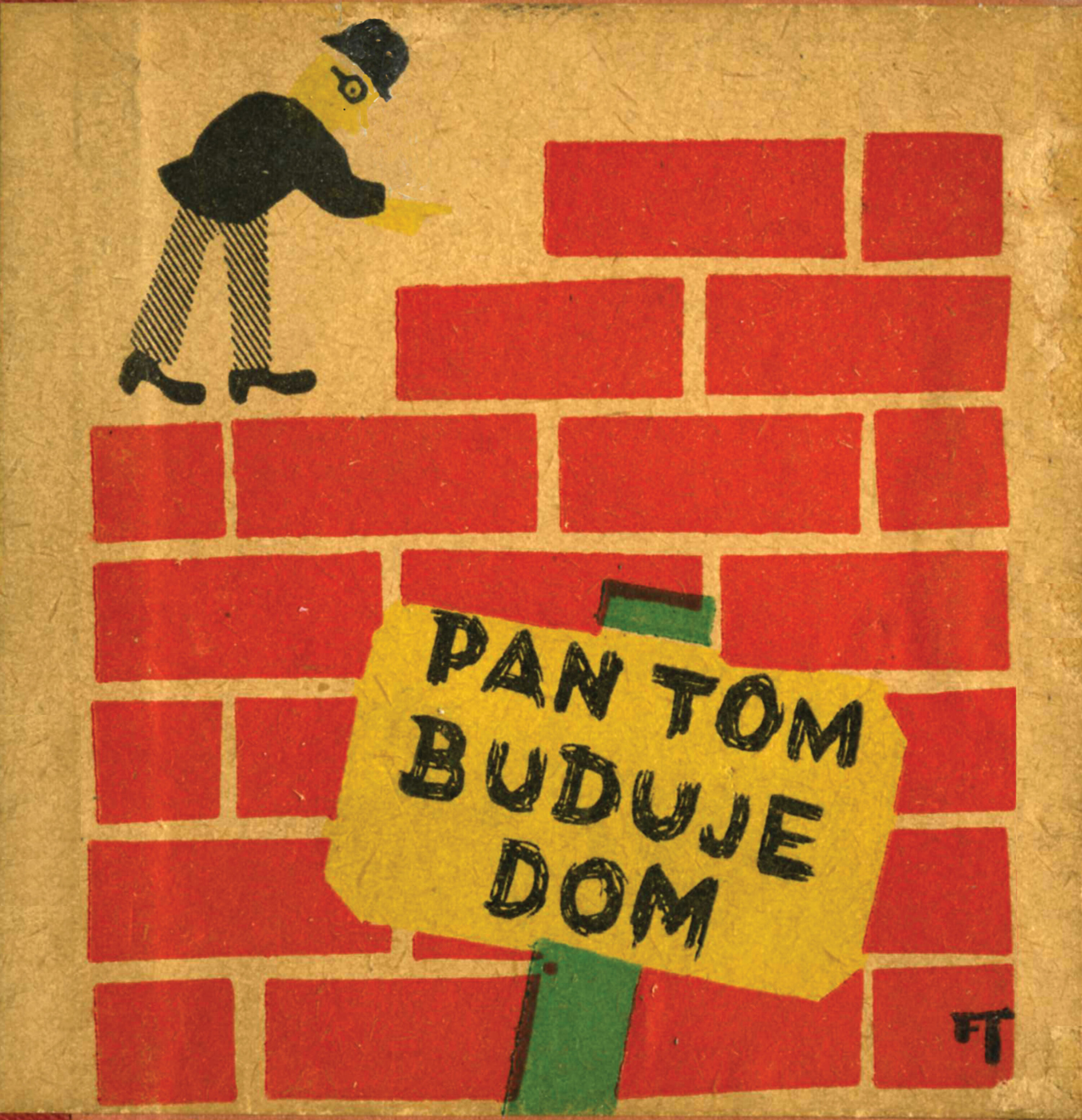

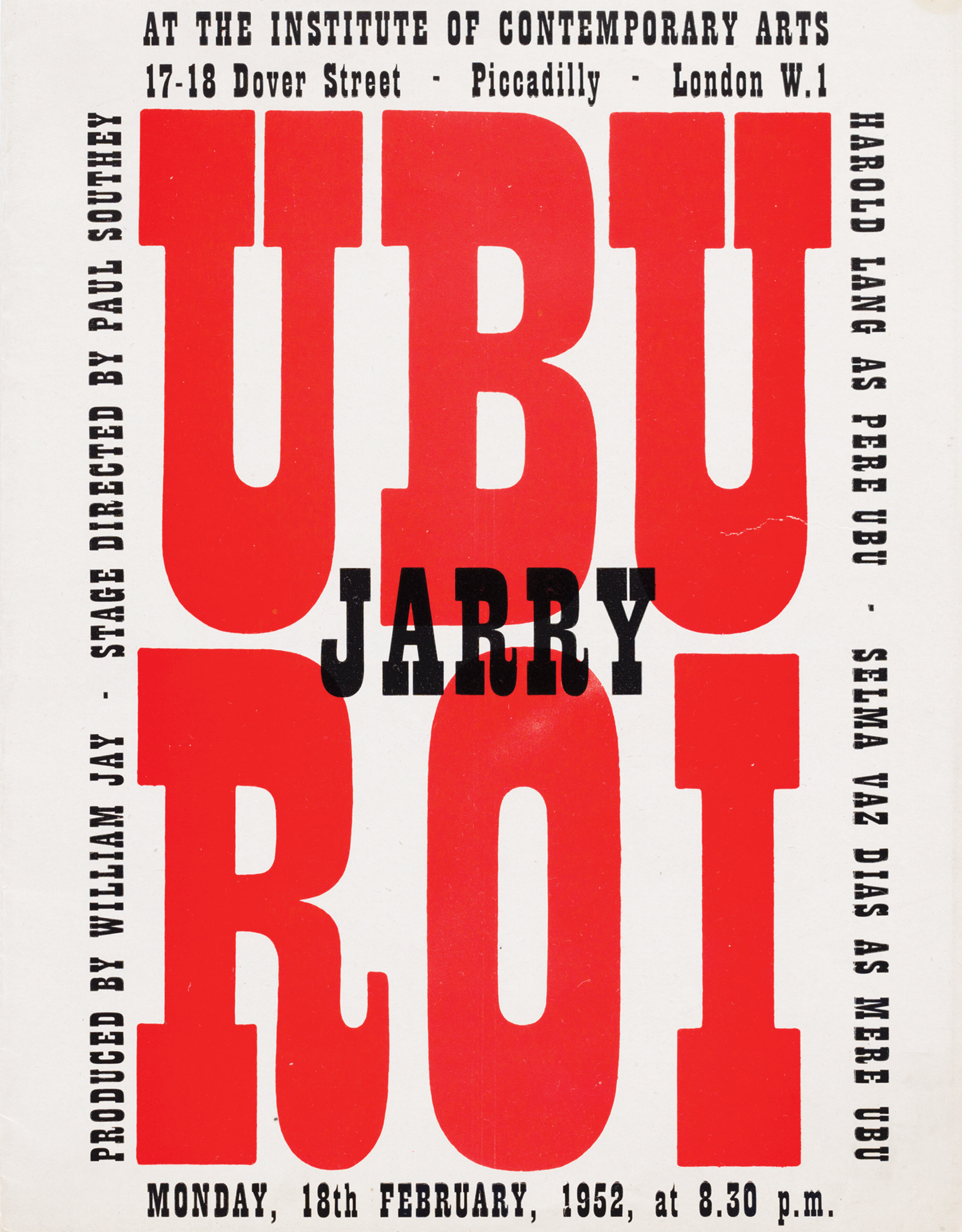

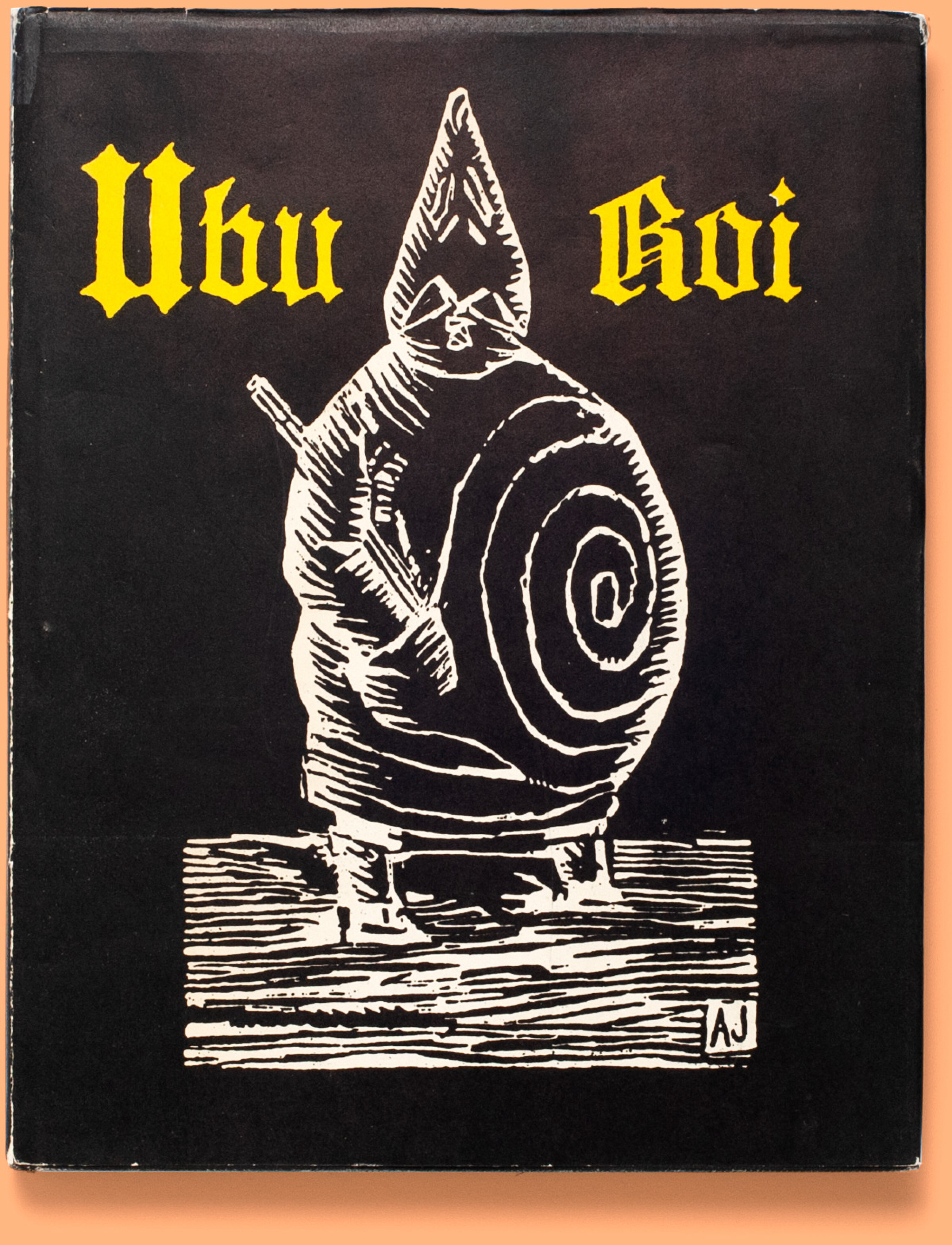

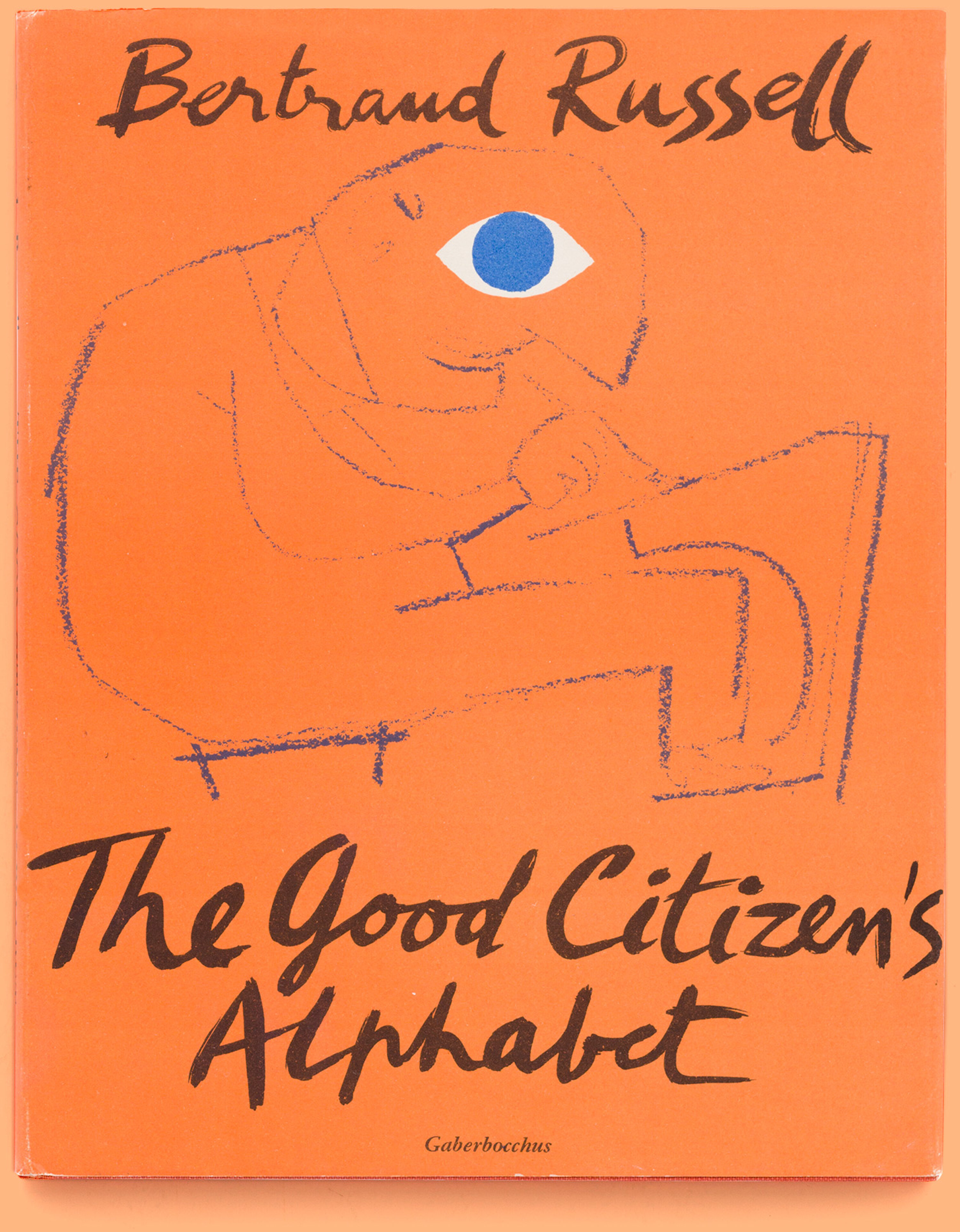

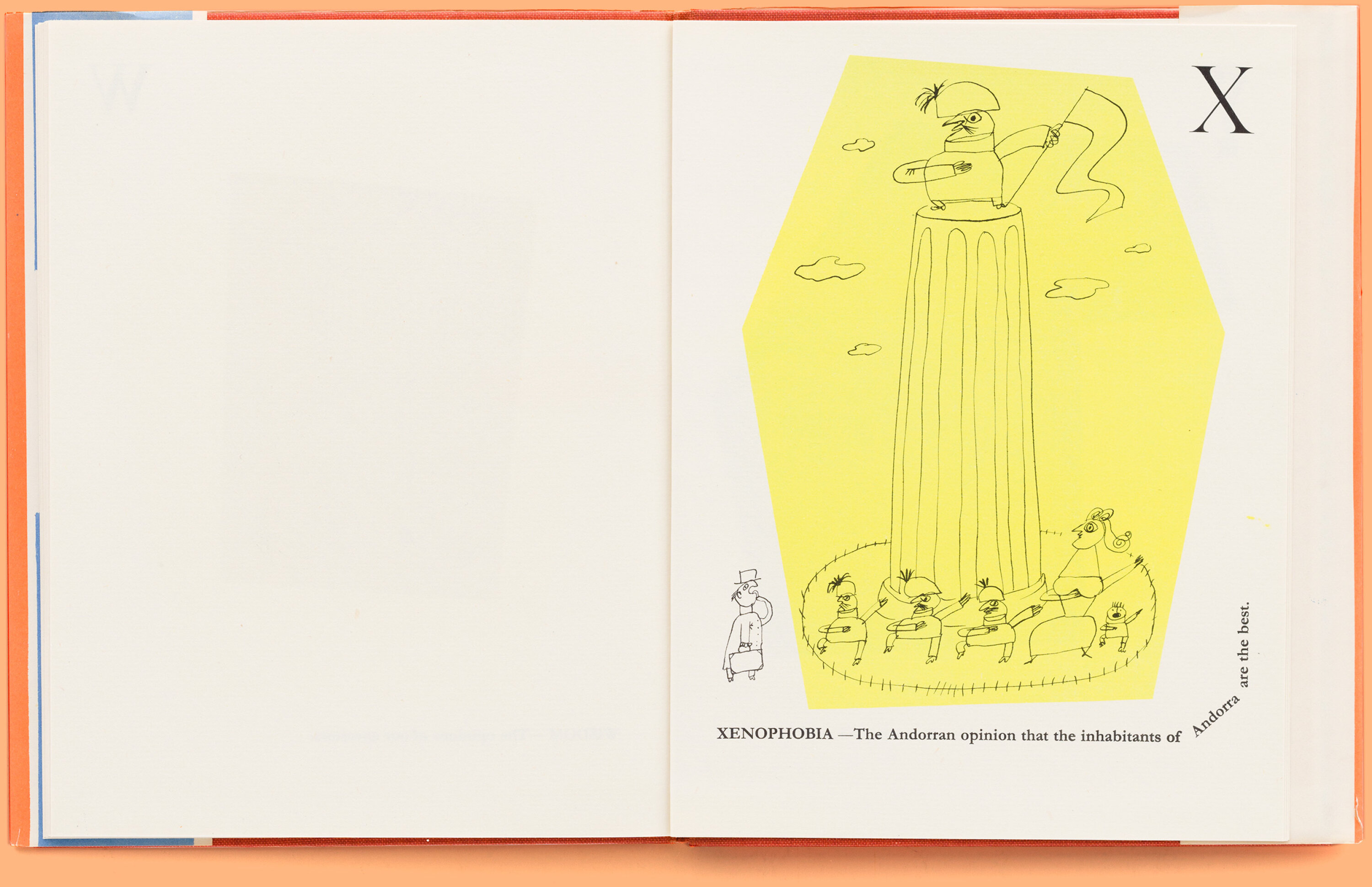

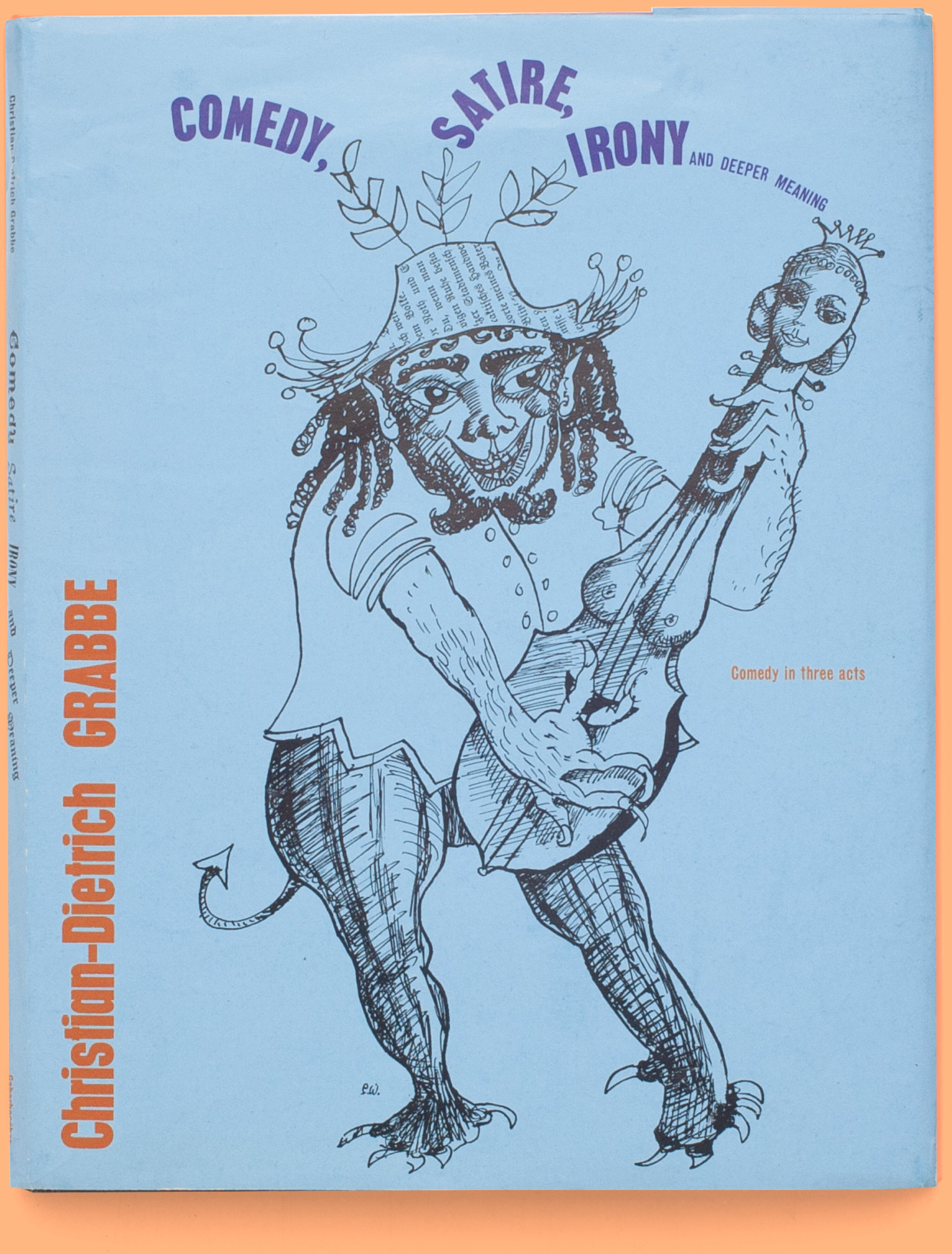

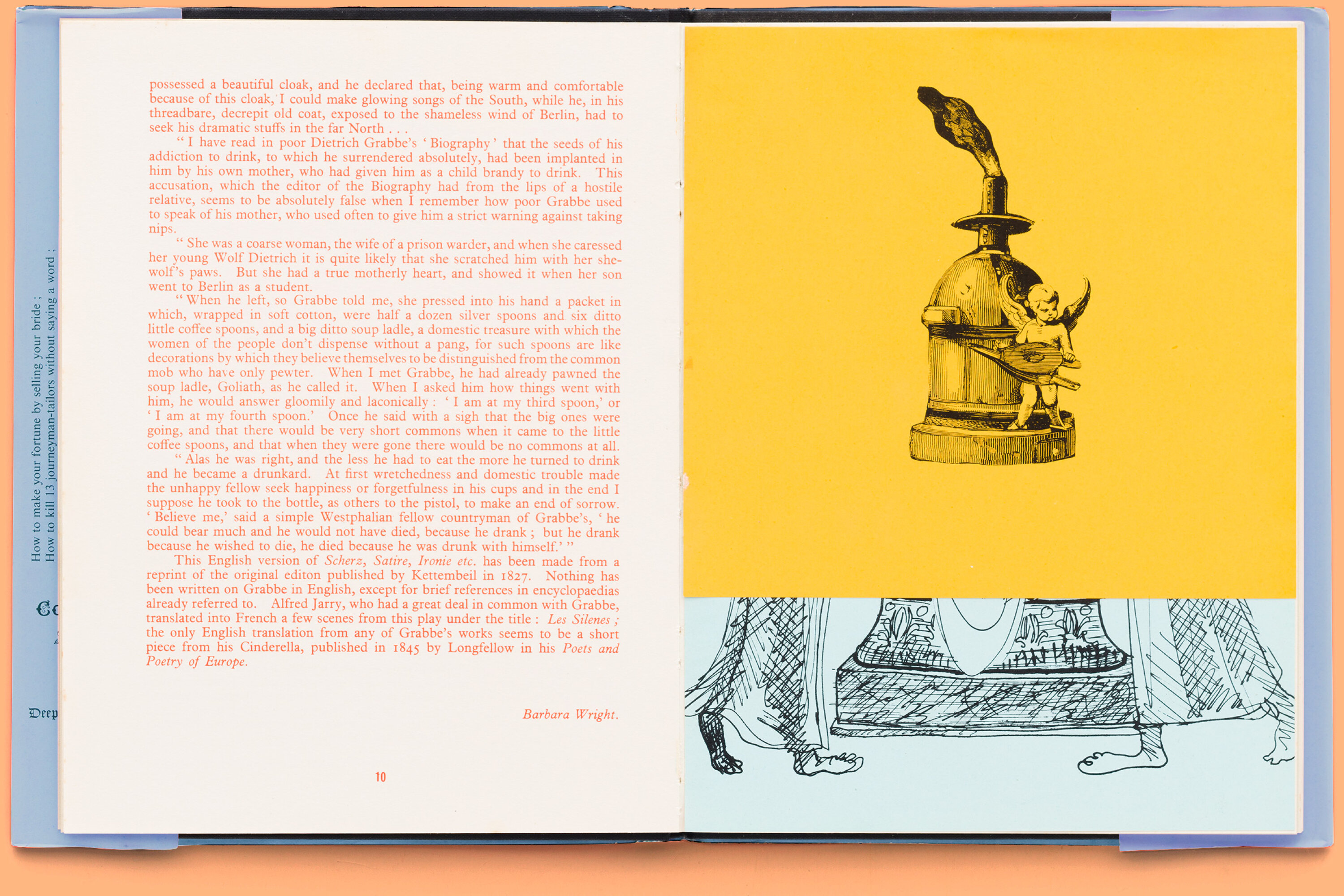

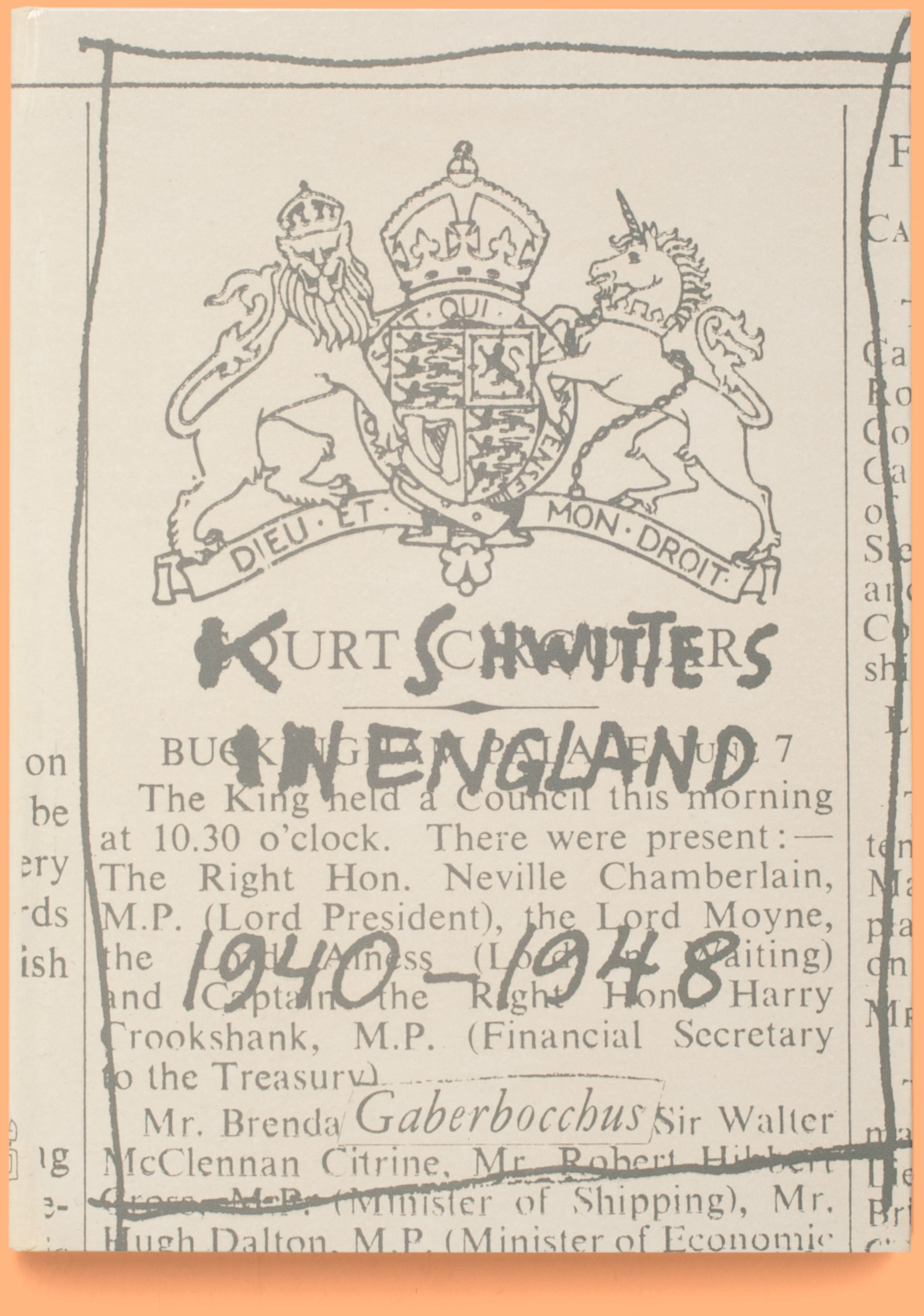

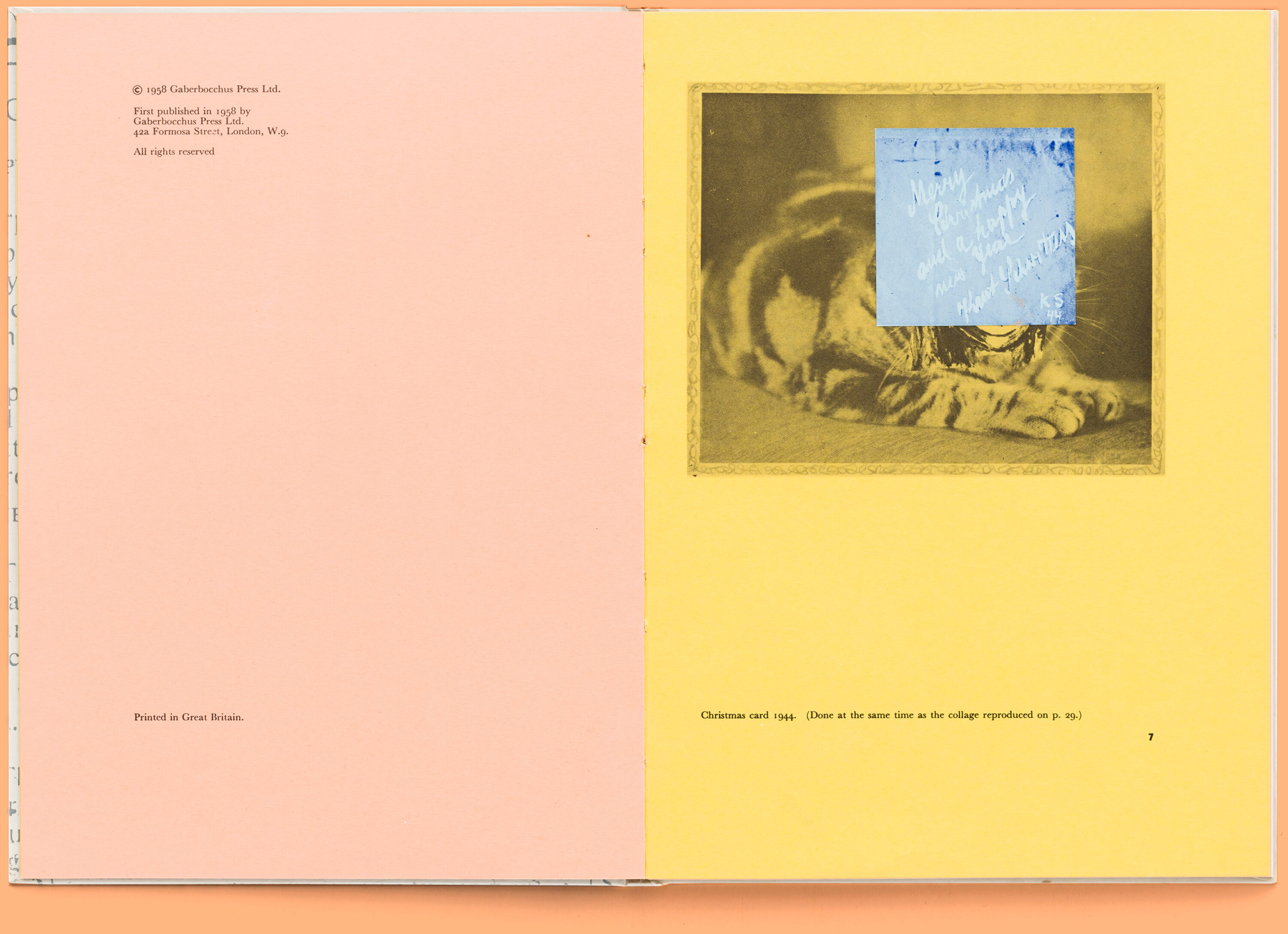

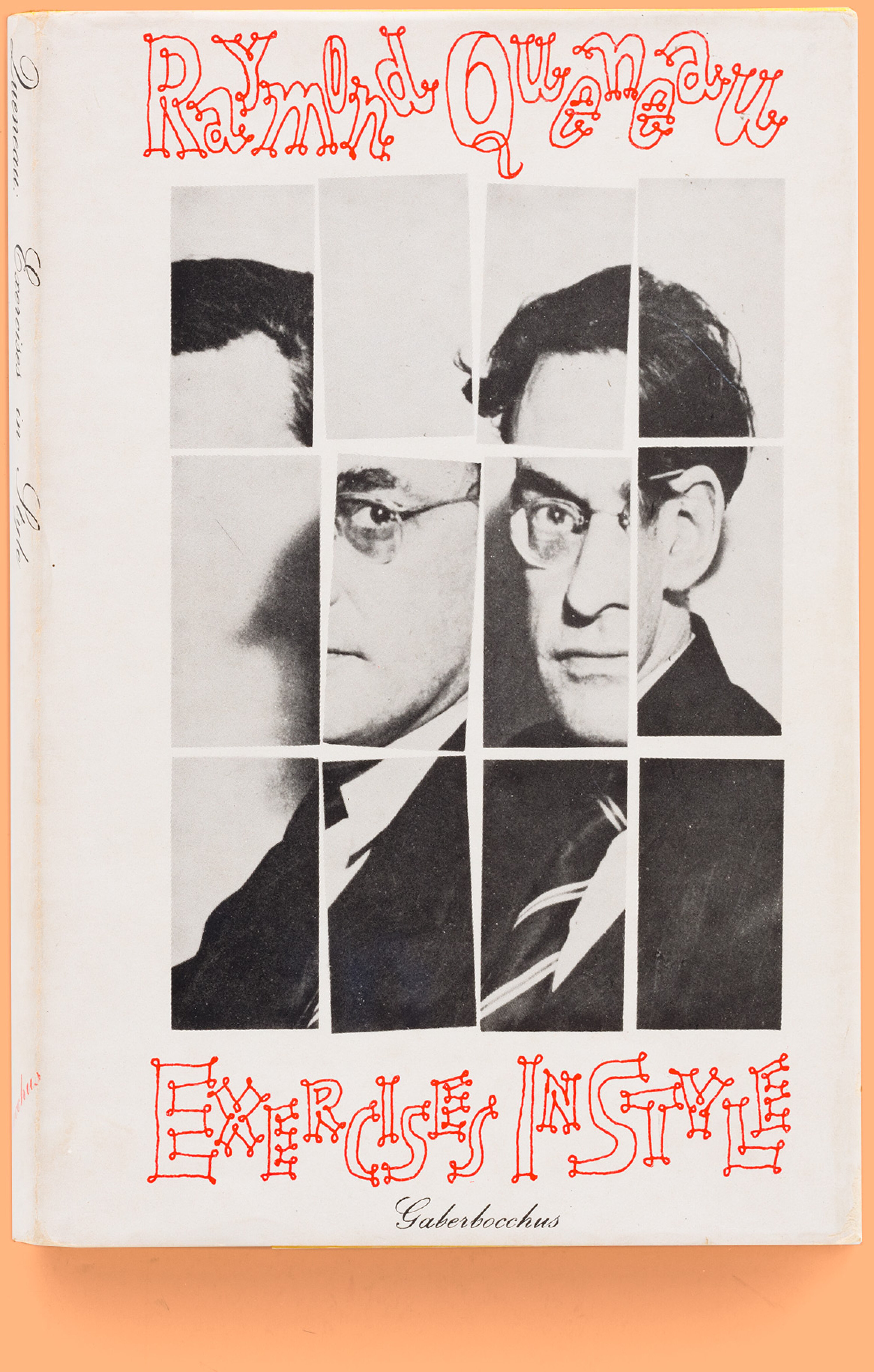

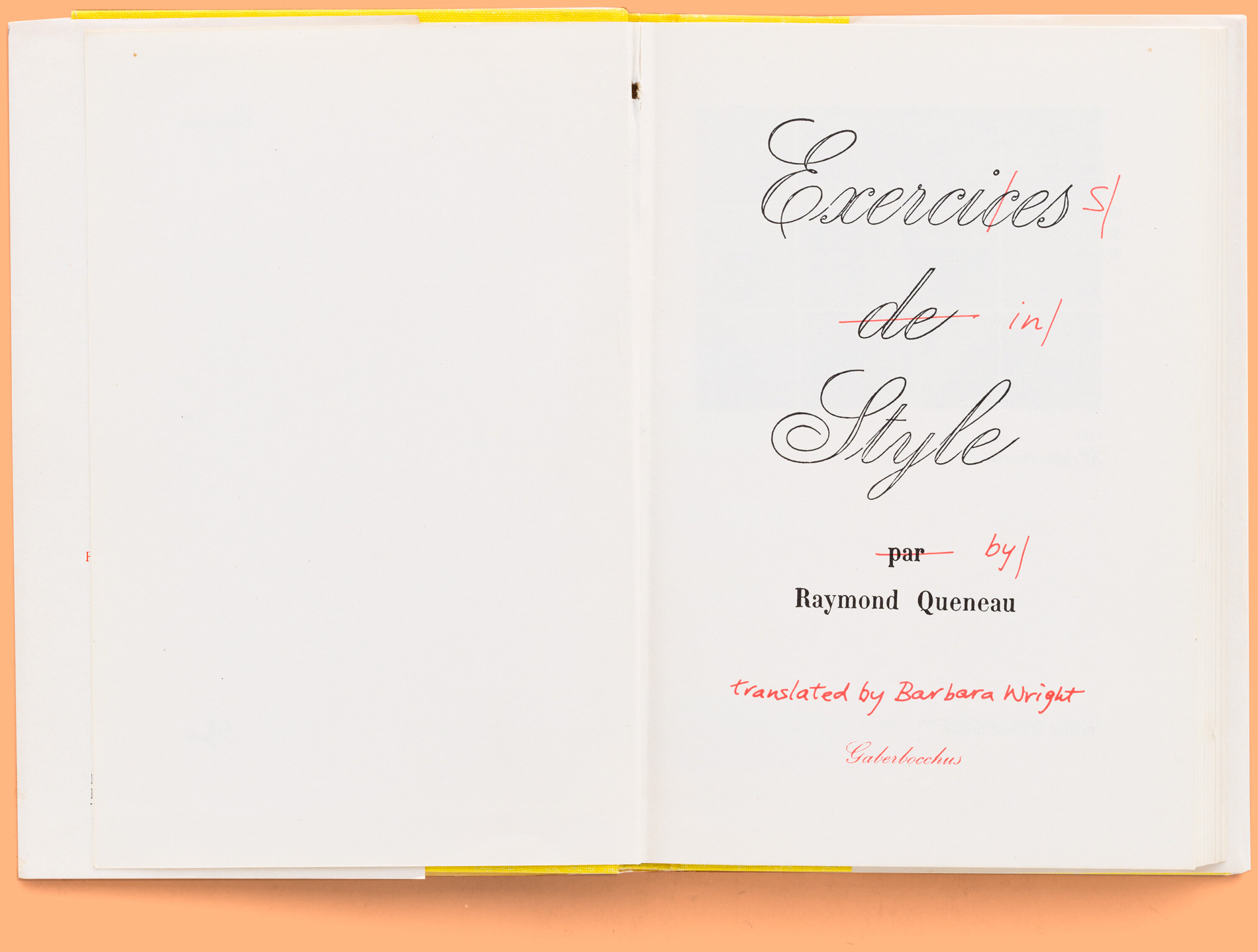

In 1948, the Themersons founded the Gaberbocchus Press. Over a period of 31 years they published more than sixty titles, including works by Alfred Jarry, Kurt Schwitters, Bertrand Russell and Raymond Queneau and by Stefan Themerson himself. As a designer Franciszka made illustrations for many of the Gaberbocchus titles. Characteristic of the Gaberbocchus Press publications were the Themersons' experiments with the relationship between text and image.

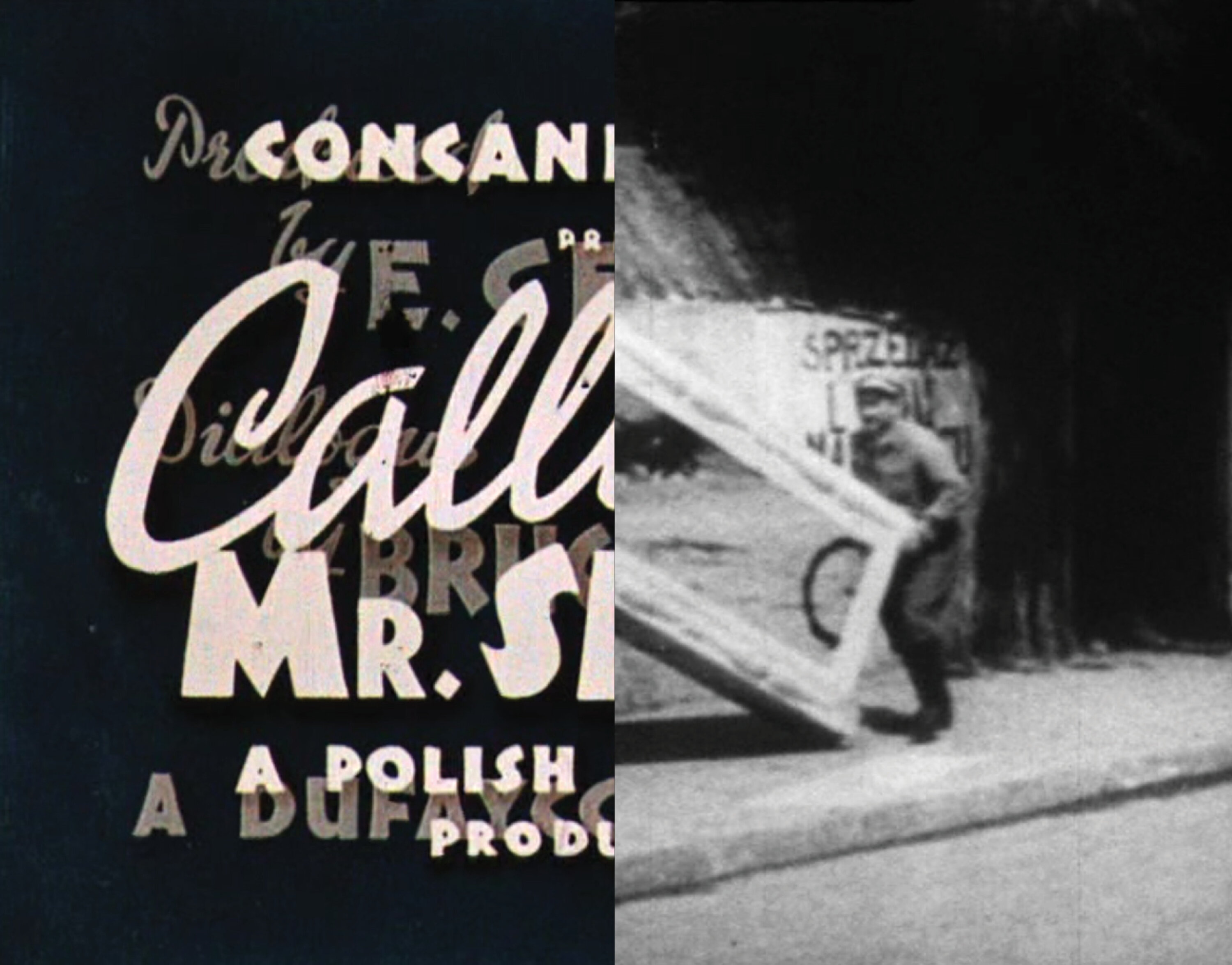

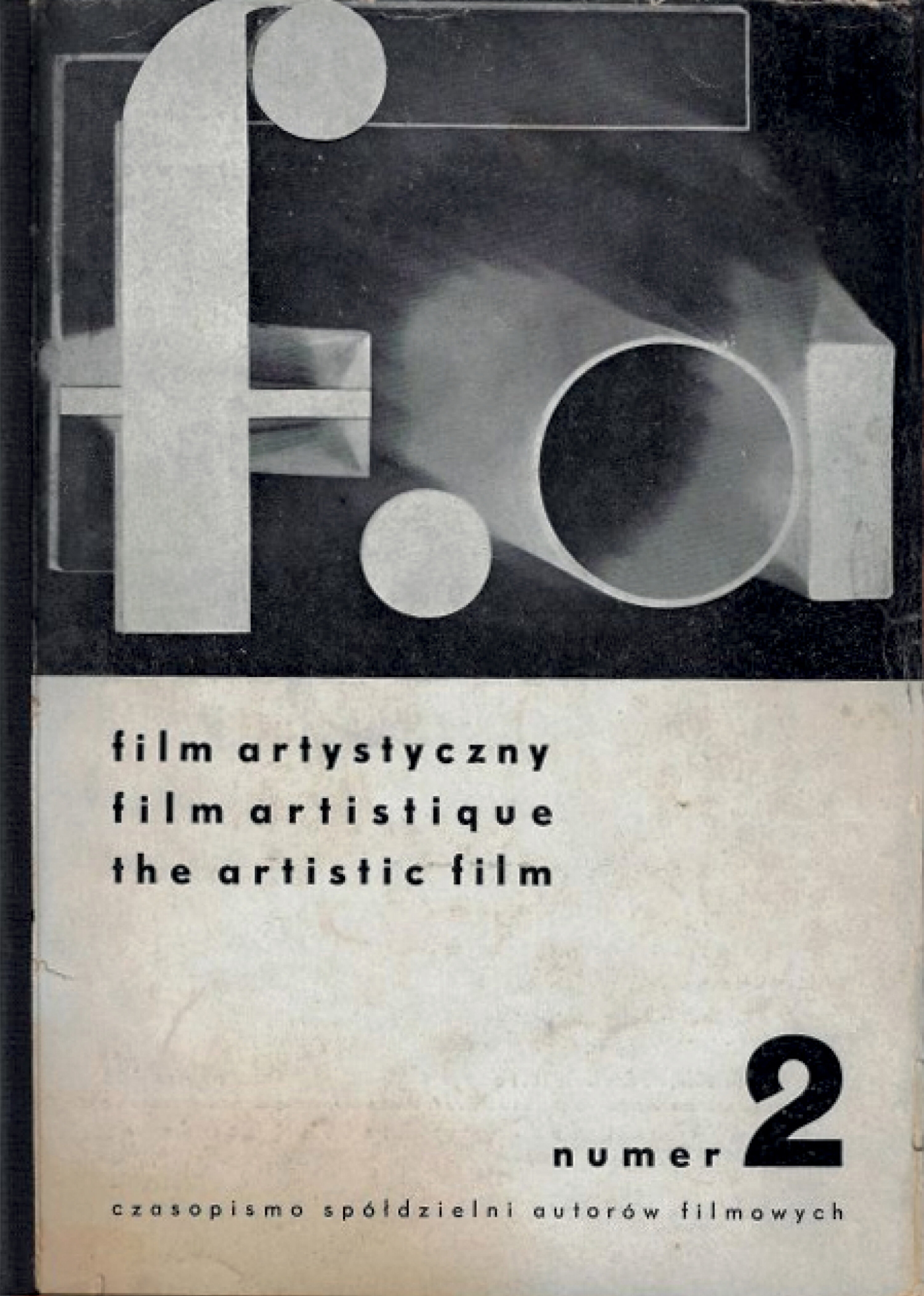

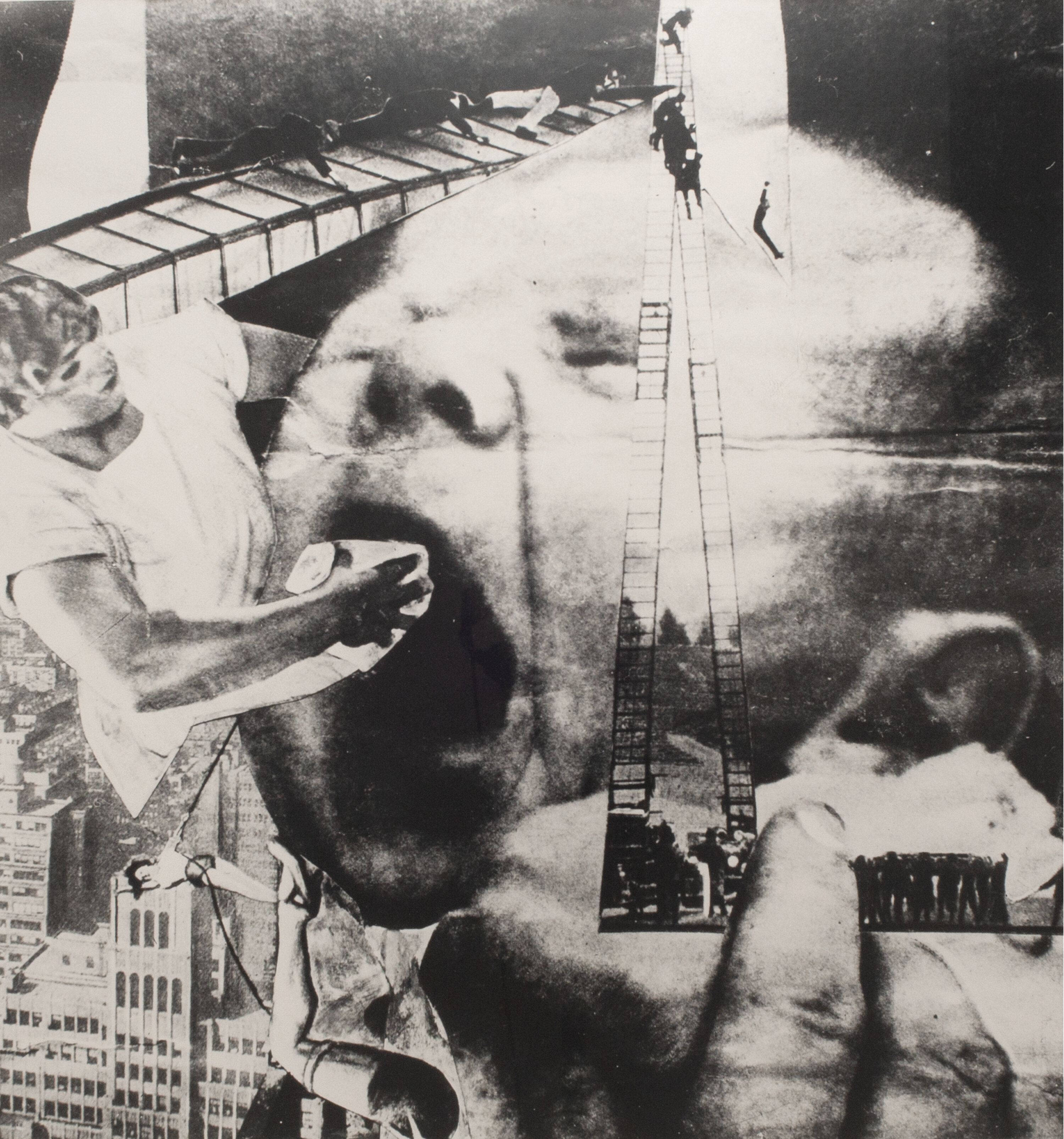

Between 1930 and 1945 the Themersons made seven short films in which their experimental photographic work from the early 1930s can be recognised. In their films they experimented with the play of light and shadow caused by moving objects, among other things.

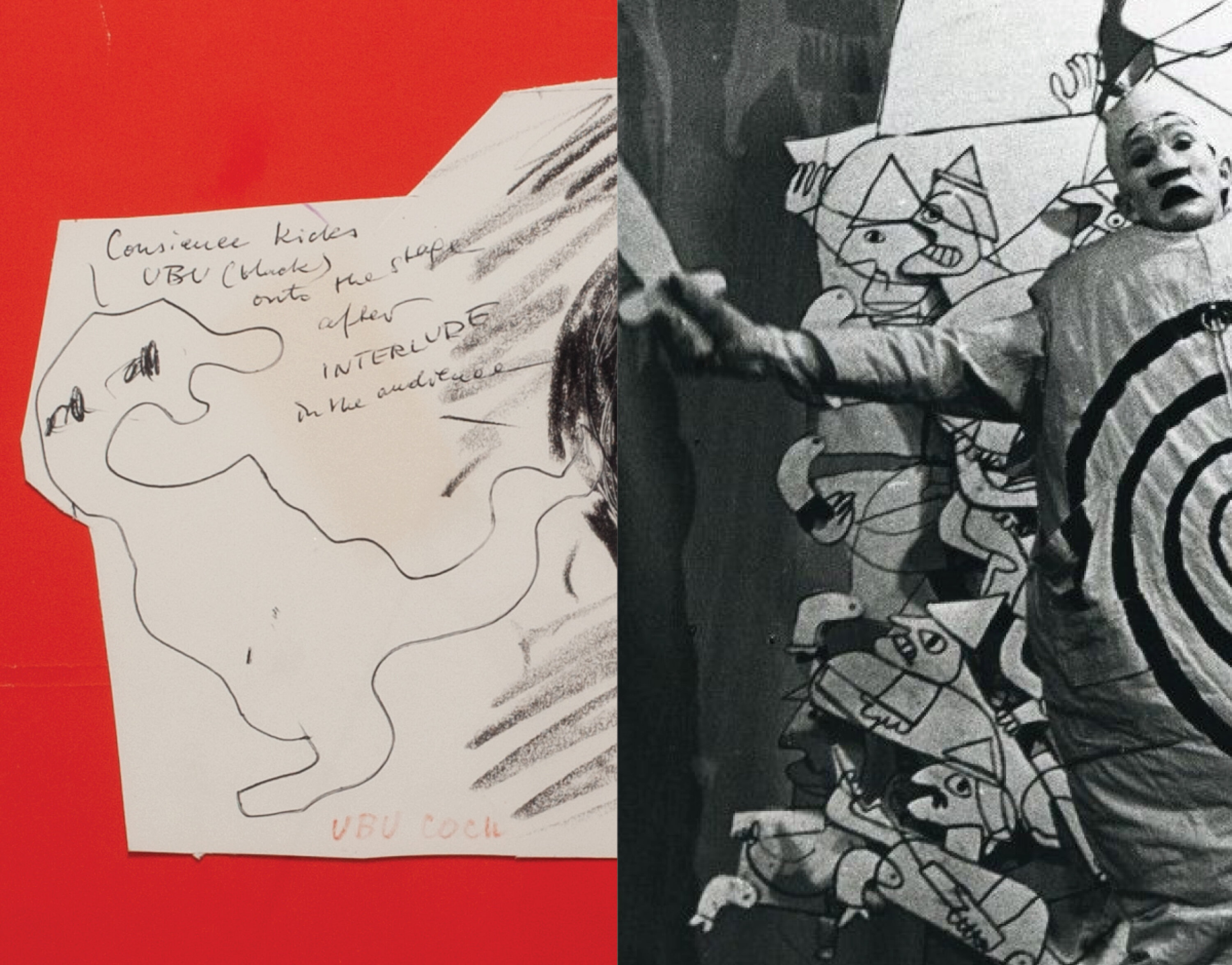

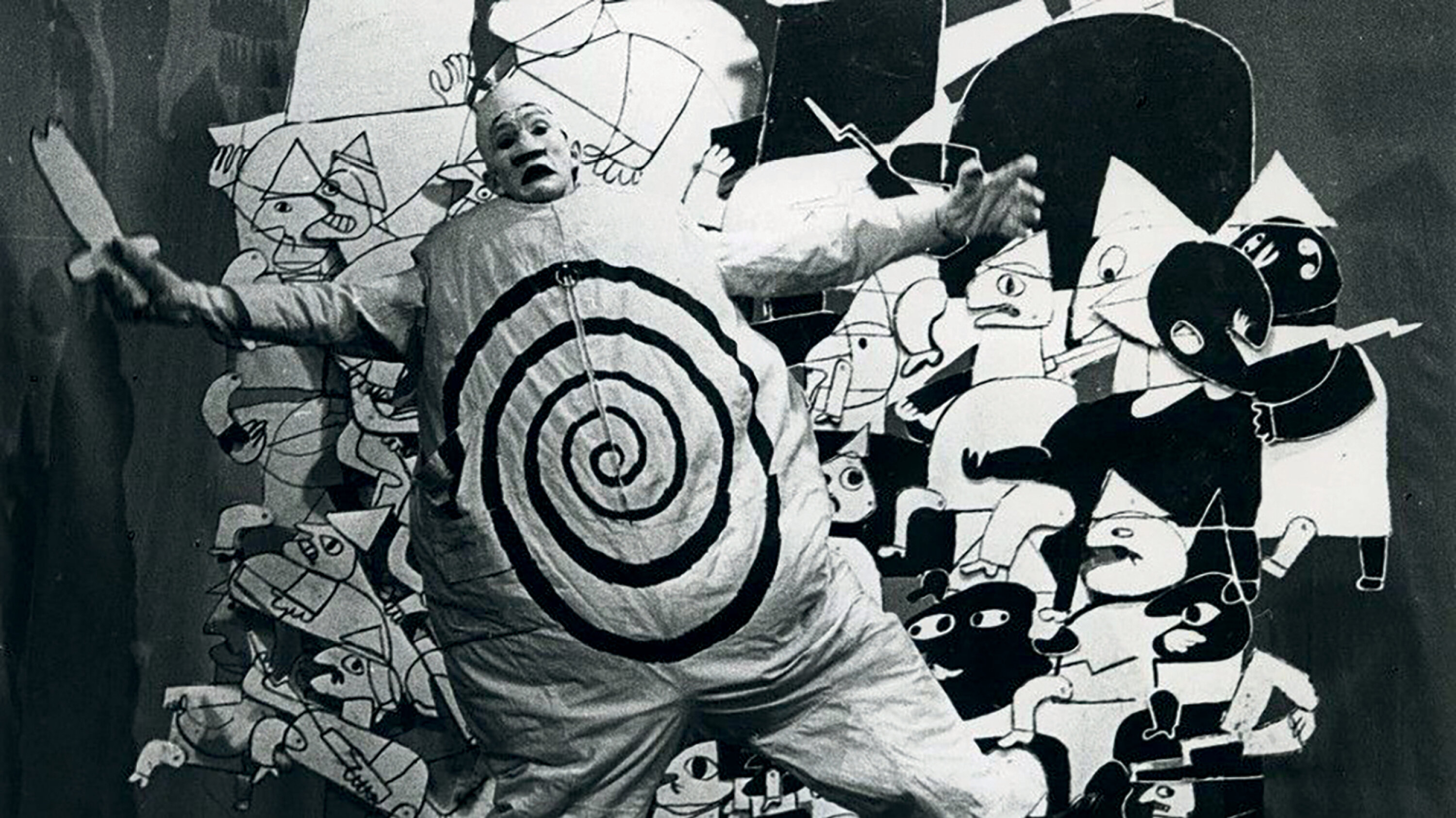

Franciszka Themerson designed the costumes and sets for the theatre productions of Alfred Jarry’s ‘Ubu Roi’ and ‘Ubu Enchainé’ and Bertold Brecht’s ‘Threepenny Opera’ in Stockholm and Copenhagen in the 1960s. She has received several international awards for her designs.

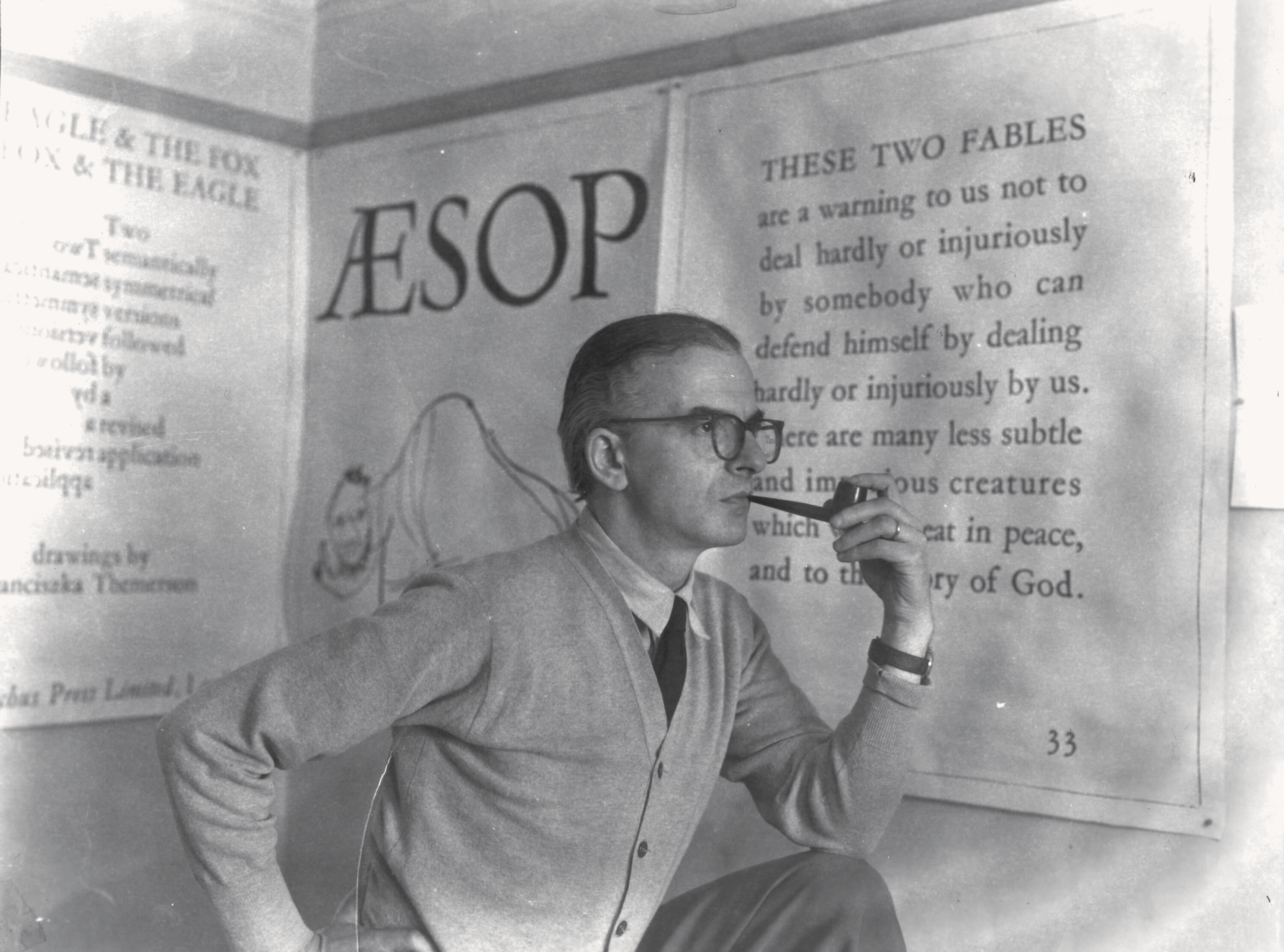

Franciszka & Stefan Themerson. A Biographical Note

Stefan Themerson, writer, film-maker and publisher, was born in Plock

on 25 January 1910, the son of a family doctor who wrote In his spare

time. He flirted with physics and architecture but became increasingly

involved with photography, collage, and film, to the eventual

abandonment of his studies. In his twenties, Themerson became well known

in Poland as an author of children’s books, most of them illustrated by

his wife, Franciszka Themerson, painter, film-maker, graphic designer

and designer for the theatre. Born Franciszka Weinles in Warsaw on June

28th 1907, she was the daughter of a painter and a pianist. She trained

as an artist and graduated with distinction from the Warsaw Academy.

Nevertheless, her first artistic achievements were as an avant-garde

film-maker collaborating with her husband. They met in 1929.

Between 1931 and 1937 the Themersons made experimental films, started a film-makers’ cooperative in Warsaw and edited and produced its journal, f.a. (art film). Stefan continued his involvement with experimental photography for which he invented new techniques. With a single exception, their films were lost during the war.

They moved to Paris in 1937 to continue their work at the center of

avant-garde activity. Their life was disrupted in 1939 by the outbreak

of the Second World War. Stefan Themerson joined the Polish Army;

Franciszka escaped to London. During the years of their separation,

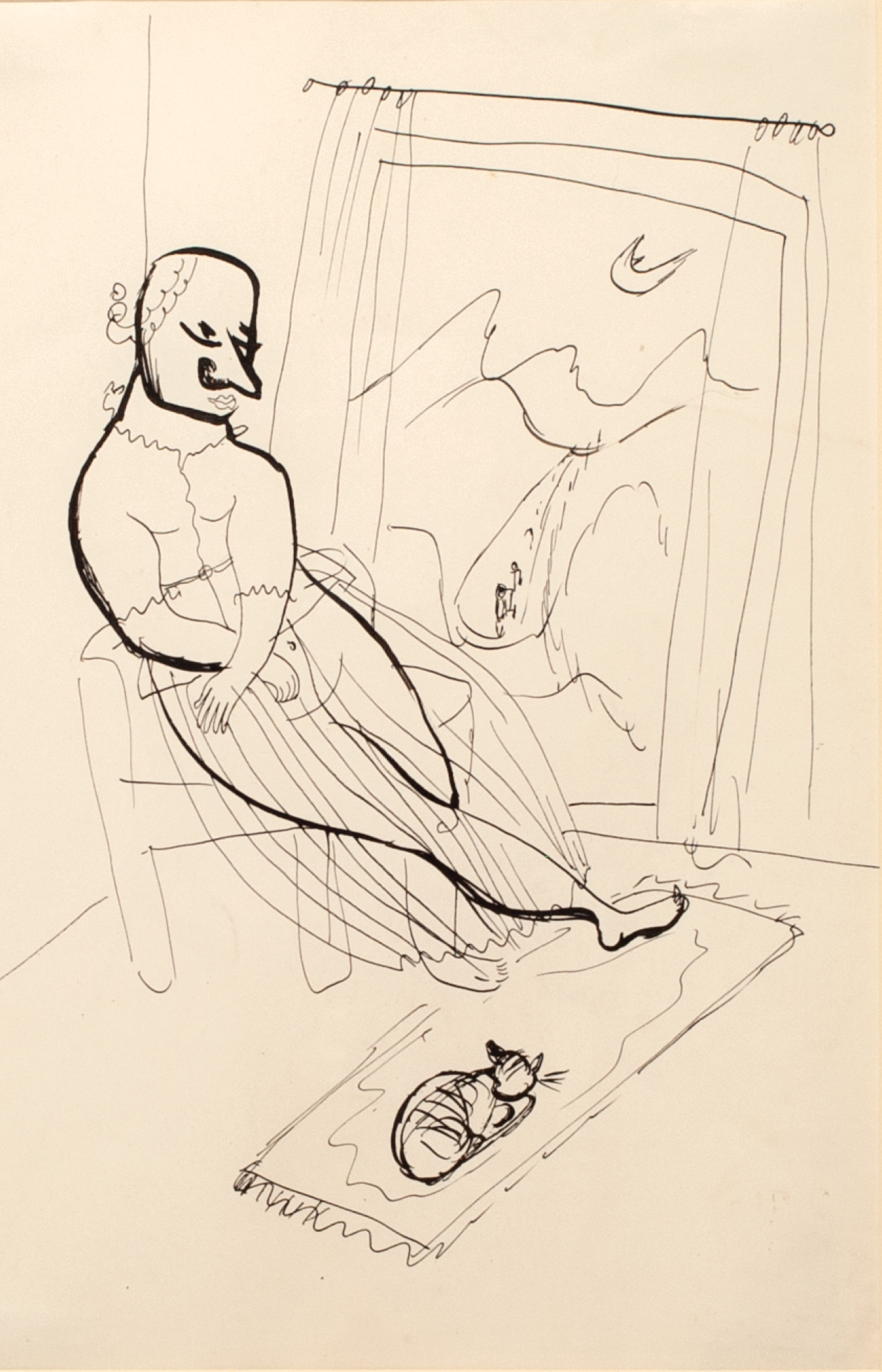

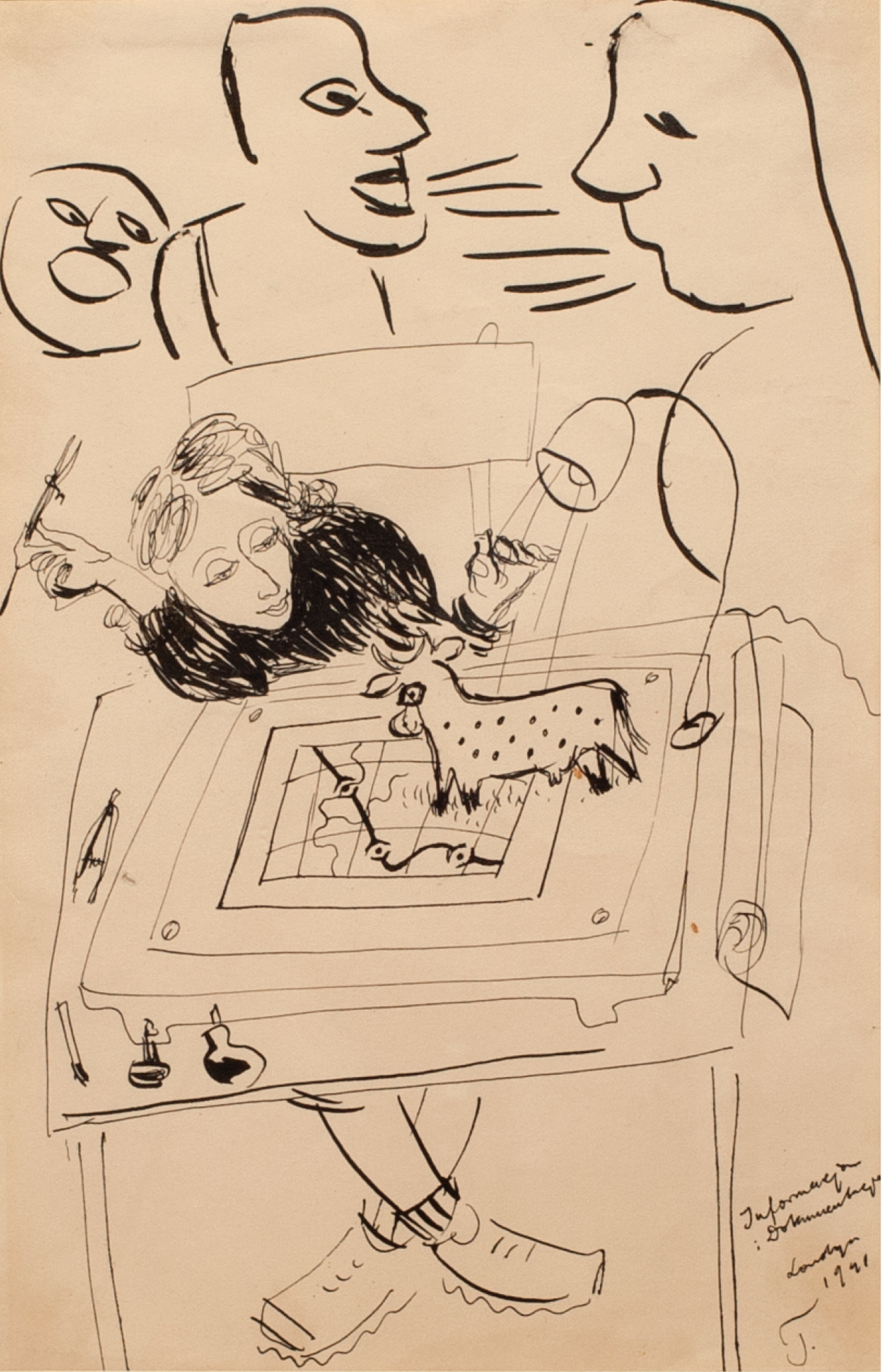

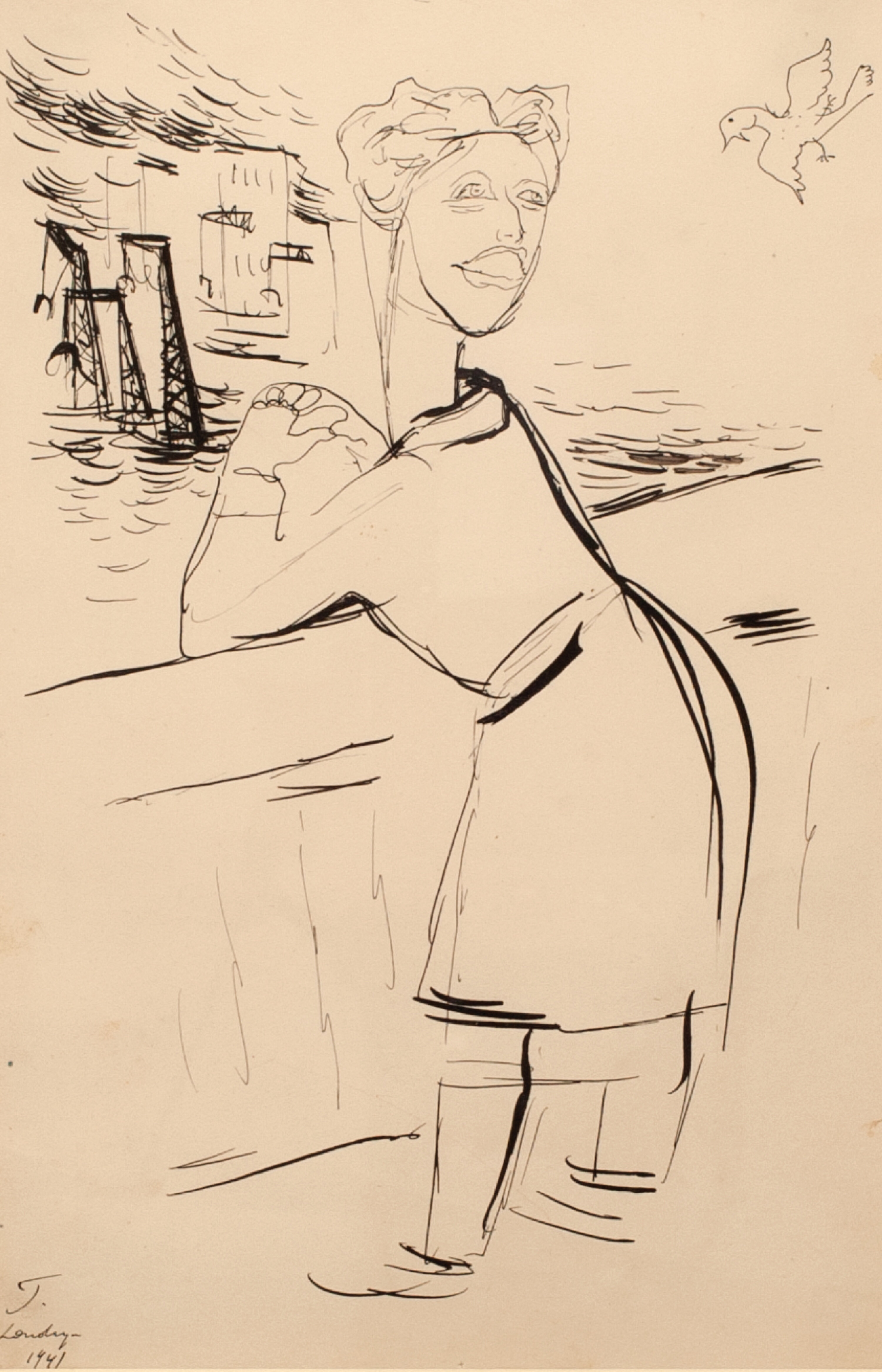

Franciszka completed a long series of drawings which she called

‘Unposted Letters’ and Stefan wrote his masterpiece Professor Mmaa’s Lecture. In 1942 they were reunited in London, where they were to spend the rest of their lives.

In London, their artistic collaboration continued first in the making of

two more films (1943-45) and then, in 1948, with the foundation of the

Gaberbocchus Press, a publishing house which over the next 30 years,

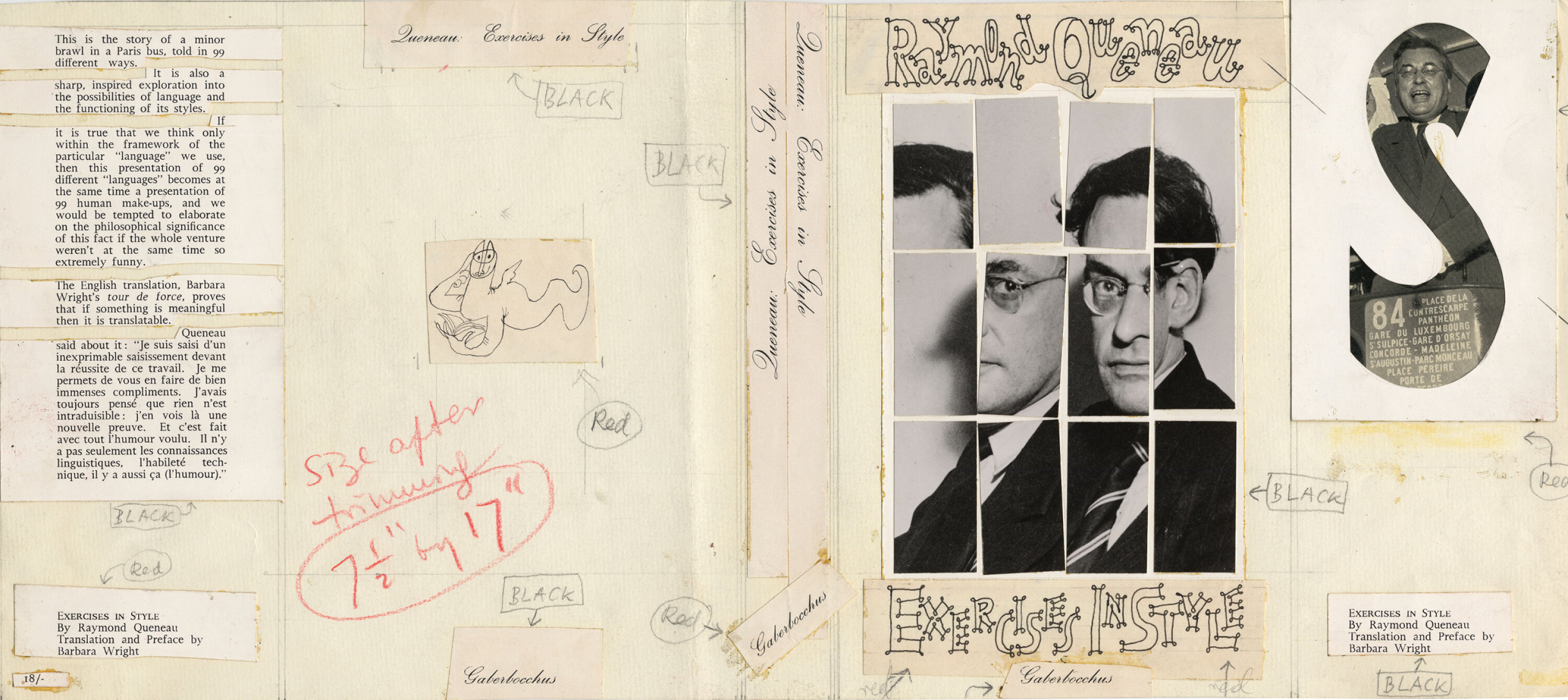

produced a string of remarkable books. These include first English

editions of Alfred Jarry, Pol-Dives, Guillaume Apollinaire, Raoul

Hausmann, Heinrich Heine, Christian-Dietrich Grabbe, Raymond Queneau,

the work of their friends Jankel Adler, Kurt Schwitters, Bertrand

Russell, Stevie Smith, C.H. Sisson, and some brilliant books of their

own. Franciszka designed the books and created illustrations for many of

them. Gaberbocchus aimed to endow the appearance of each book with

qualities inspired by the content.

Franciszka’s mature career as a painter developed from the late 1940s. From 1957 there were major exhibitions of her paintings and drawings in galleries and museums in London, New York, Belfast, Poland and Denmark. Among public collections holding her work are Museum Narodowe, Gdansk; Museum Sztuki, Lodz; British Museum, London; London Film-makers’ Cooperative; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Marionettemuseen, Stockholm; Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw.

During the 1960s, she did outstanding work in theater design, including sets for Ubu Roi (1963-64) and The Threepenny Opera (1966) at the Marionetteatern, Stockholm. In 1970-71 she designed Ubu Enchainé and Thesmopharia Zusai for the Dukke Theatre, Copenhagen. She was awarded the gold medal at the 1966 Triennale of Theatre Design, Novi Sad, and, in 1976, elected honorary member of Union Internationale de la Marionette for her services to the theater.

Over the years, her paintings became paler and more aggressive. The line which carries the image is incised, scratched or gouged out of the surface. Pigment is allowed to seep into the gaps. Drawing, in whatever medium, remained a constant and primary activity throughout her career, and in retrospect appears to have been her abiding passion. She contributed drawings to journals throughout her career, in Europe and elsewhere, and several collections of her line drawings were published as books: The Way It Walks (1954 and 1958), Traces of Living (1969), Franciszka Themerson 1941-42 (1987). Her originality as a designer was also expressed in her exhibition design, and in her teaching at Bath Academy of Art and Wimbledon School of Art.

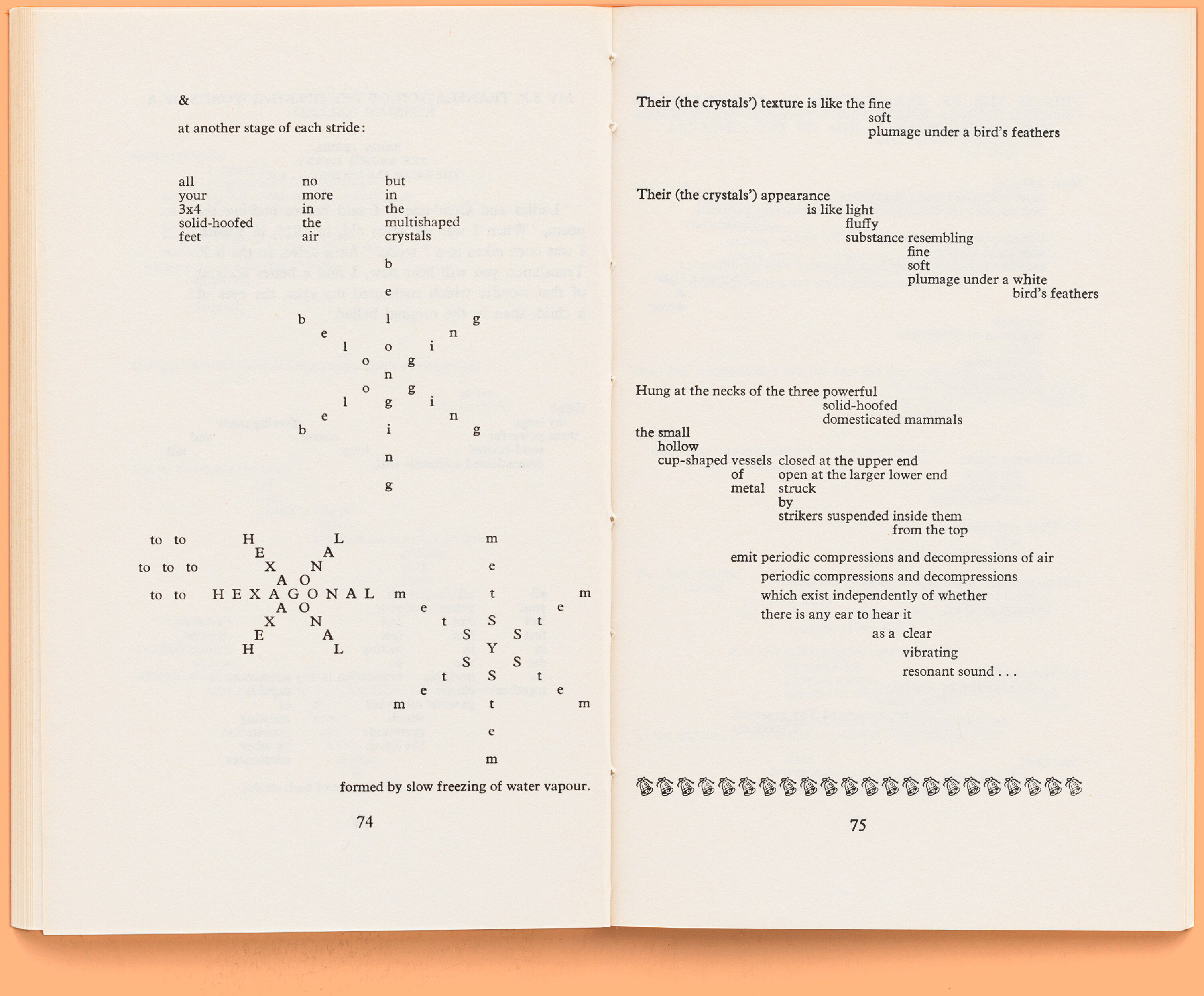

Whereas Franciszka’s medium of paint, line and color is free of rules, Stefan’s is confined by formal demands of grammar and of the three languages in which he worked – Polish, French and English. The last was his principal language but he often made his own translations from one language into another. He wrote 9 philosophical novels, but was not a conventional novelist. He wrote 12 books for children, but these too are unlike other books for children, introducing the young reader, as they do, to the magic of the real world. He wrote poetry, essays, some texts on art, one play, the libretto and music for an opera – St. Francis and the Wolf of Gubbio – and a book about photograms and experimental cinema. All of his writings share a concern with ethics and language. His concern with ethics is encapsulated in the Chair of Decency, the Huizinga lecture delivered in Leyden in 1981 which argues that there is no aim greater than the decency of means. His concern with language is encapsulated in Semantic Poetry which he invented in 1944. Semantic Poetry is the sort of poetry that returns at every step to pure dictionary definitions of words and banishes the euphemisms, local color and contextual overtones with which usage shrouds them. Themerson disliked classifications and he himself remains unclassifiable.

His books have been translated into eight languages. A comprehensive bibliography of Stefan Themerson is published in Comparative Criticism, Cambridge University Press, 1999. ‘Bibliography is my biography,’ he said, ‘the rest is irrelevant.’

Franciszka died in London on June 29th 1988, Stefan Themerson on September 6th 1988. The Themerson Archive, which was at 12 Belsize Park Gardens in London from 1988, moved to the National Library in Warsaw in December 2014.

A Bibliography of the Gaberbocchus Press

‘There is a madness about various Gaberbocchus books which is the spice

of life, an ingredient somewhat lacking in the world of impeccable book

production,’ Ruari McLean wrote in the Summer 1956 issue of

the Quarterly News-Letter of the Book Club of California. ‘Not

best-sellers, but best-lookers’ was how Stefan and Franciszka Themerson

described the books they aimed to publish. This was ‘sound economic

policy’ for a small publisher, they declared in an article for The

Bookseller. The symbiotic relation between this Polish-born, British

couple, who between them combined the disciplines of philosopher,

writer, painter, illustrator, graphic designer, filmmaker and publisher,

produced a catalogue of publications that is remarkable in every sense

of the word. When the Themersons founded the Gaberbocchus Press in 1948,

they did so mainly in order to publish what they wanted, not least

their own work, in the forms of their choosing. Gaberbocchus is a Latin

translation (by Carroll’s uncle) of ‘Jabberwocky’, Lewis Carroll’s

nonsense poem about a fabulous creature called the Jabberwock. Themerson

said later, ‘Our friends thought that Gaberbocchus might well be a fine

Latin rendering of Jabberwocky, but that as the name of a publishing

house it just wouldn’t do! Indeed, it does look rather difficult to

pronounce. And yet the strange thing about it is that no-one who had

once got it straight, can ever forget it again. […] We have proved that

this strange animal cannot go on living without publishing what is very

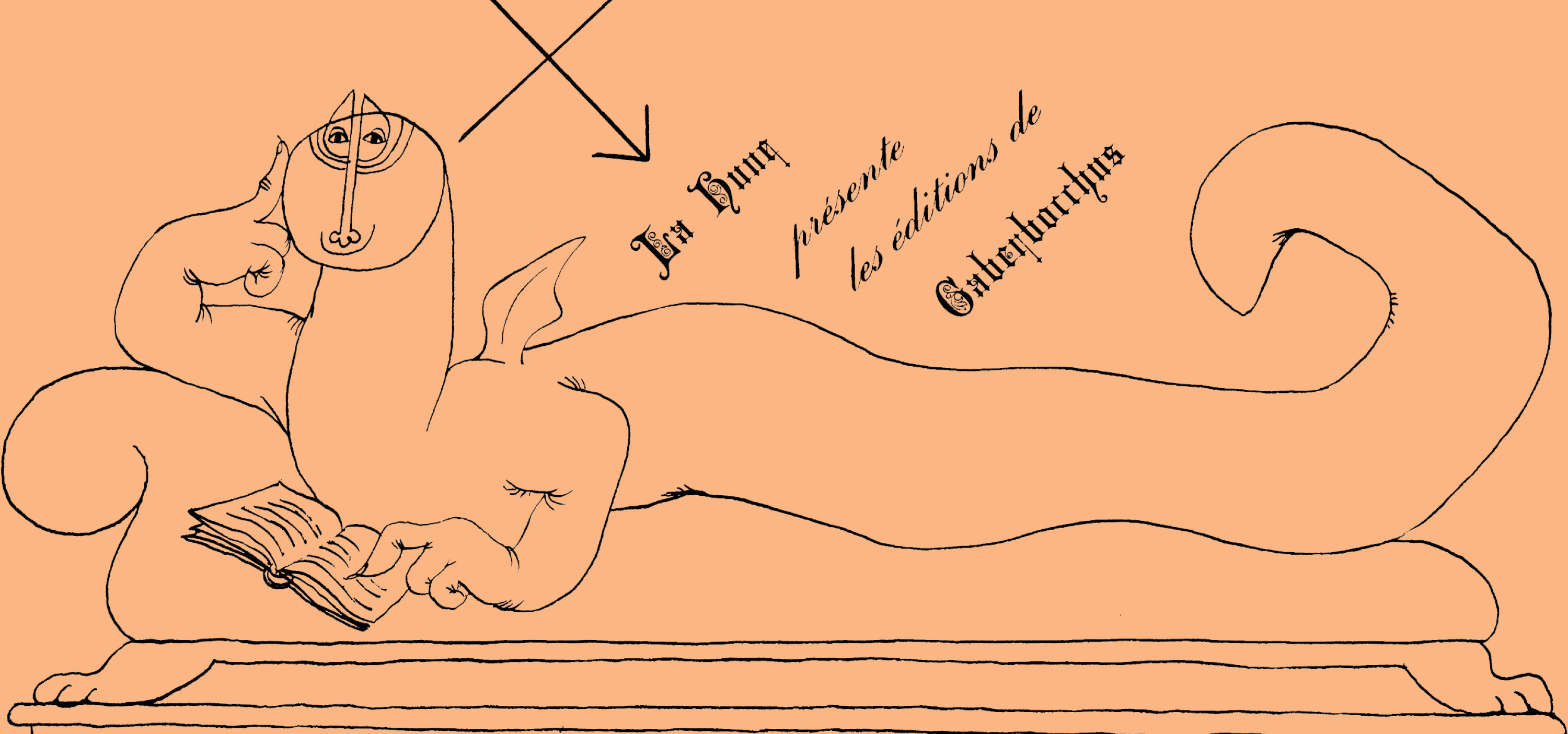

near to his manxome heart’. Franciszka’s logo of the press depicts

Gaberbocchus as a friendly little dragon, shown with various attributes,

such as a book, or a fountain pen wielded in the manner of a sword.

When asked about the strengths and weaknesses of the Press, Themerson

gave the same, unequivocal answer to both questions: ‘Refusal to

conform.’

Although the work of Franciszka and Stefan Themerson clearly has

roots in the international avant-garde of the interbellum, they

maintained a high level of independence in all of their activities. The

first Gaberbocchus books were printed by the Themersons on a handpress

in the corridor of their London flat. Their publications are

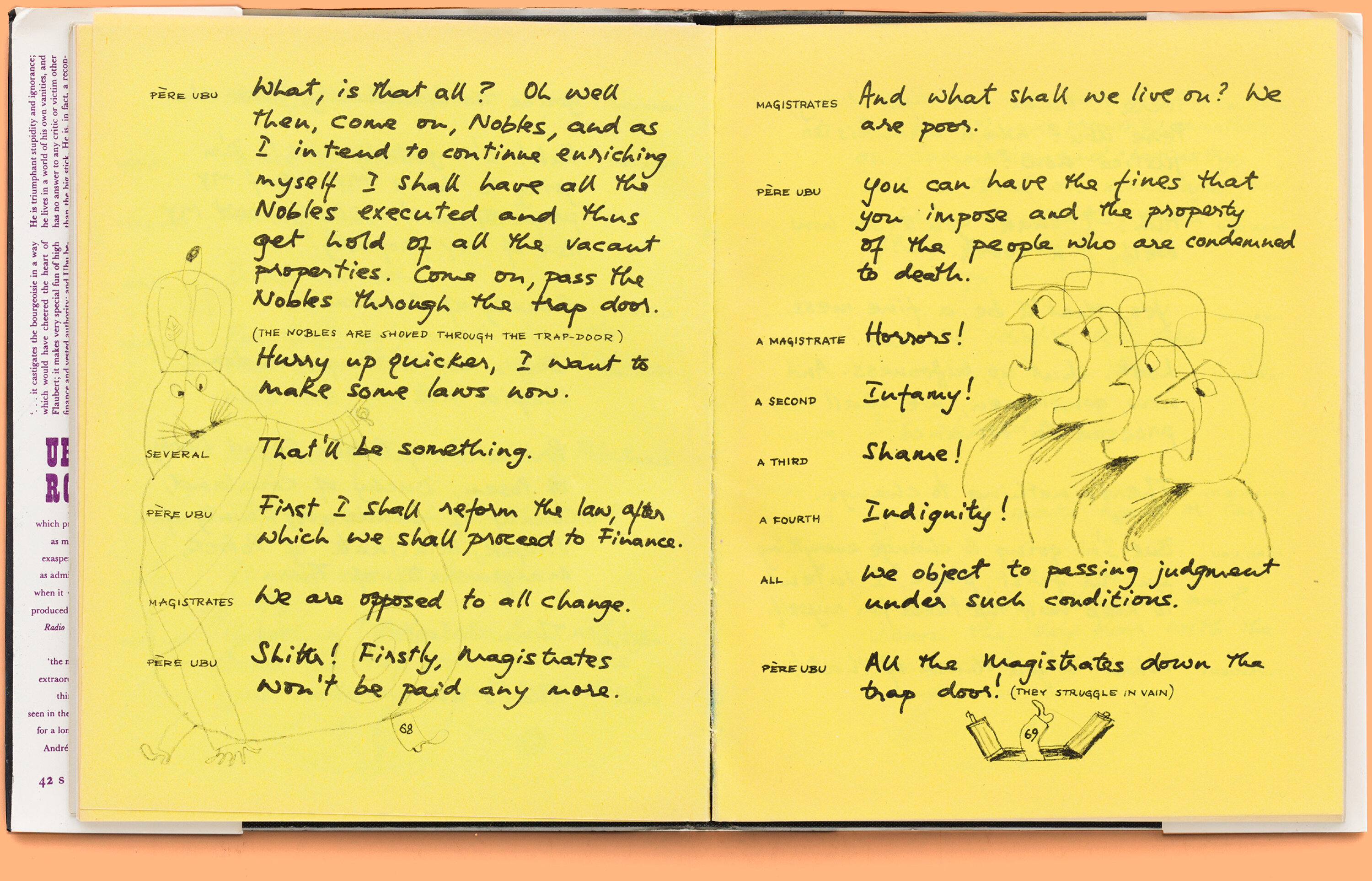

characterized by all manner of improvised techniques and materials, and

by experiments with word and image. They often used cheap printing

techniques (such as Rotaprint, an offset process) and job lots of

colored papers at sale prices. The required negatives were made by

Themerson with a second-hand camera. It has been said that Gaberbocchus

did not have a ‘house style’: what connects the sixty or so titles

published by the Press between 1948 and 1979 is their unique

combinations of text, image, design and materials. The books exude a

gentle non-conformism and eccentricity, expressing the identity of its

contents. Their family unity springs from the degree and quality of each

book’s originality, and Stefan playfully drew a ‘family tree’ of

Gaberbocchus books and their authors. As well as their own work, and

translations of important experimental European writers unknown in

England, they published work by British writers and artists, who worked

mainly on the periphery (many of whom became friends – like Stevie

Smith, George Buchanan, Patrick Fetherston, C.H.Sisson). Financial gain

was never the driving motivation of the Press. As Barbara Wright wrote,

‘No one ever thought of money in those days except insofar as some was

needed to be able to publish.’ Wright, who started her career as a

translator with Gaberbocchus, was one of the four directors of the

Press, as was the artist Gwen Barnard. Lack of funds meant that many

projected books remained unpublished, including works by Henri Michaux,

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz, Douanier Rousseau, Bertrand Russell, and an

illustrated dictionary of semantically interpreted terms.

One plan that was realized was the Gaberbocchus Common Room, a ‘club’ founded by the Themersons in 1957, to bridge the gap between art and science by offering those from each culture a place to meet. Categories and boundaries were considered anathema. There were film-shows and recitals; lectures, plays and poems were delivered, art works and scientific objects exhibited, meals shared. In all 82 evenings were organized, and the membership reached 149. Stefan gave a lecture on Kurt Schwitters in England, Franciszka a talk on her pictorial language, Barbara Wright introduced the work of Raymond Queneau. The adventure ended prematurely, through lack of funds. In 1959 doors closed for the summer and never reopened.

The Themersons’ particular interest in book design and the printed

page is witnessed by their contact/friendship with such well-known

typographers as Anthony Froshaug and Herbert Spencer, whose celebrated

review Typographica published several articles by Stefan, including his

typographical masterpiece, ‘Kurt Schwitters on a time-chart.’ In the

1965 issue of The Penrose Annual, the graphic yearbook also edited by

Spencer, Stefan set out his ideas on what he called ‘typographical

topography’ in a Socratic dialogue between the author and a dog named

Brutus, about the appearance of the printed page. He argues that

standardisation of page lay-out has led to an ‘unjustified’ type-setting

that has lost all its distinctive character – so that we no longer

recognize at a glance what kind of text we are dealing with. ‘A page of a

book’, the author says, ‘is like a human face.’

This dialogue forms the introduction to ‘Printers and Designers’, the typographical adaptation of a lecture that Spencer composed on an electric typewriter. Spencer’s text is an ode to the book as a means of communication; to the possibilities of the printed word; and an incitement to printers and designers to experiment. In ‘Printers and Designers’, Stefan takes the opportunity to apply his own Semantic Poetry – invented and developed earlier in his novel Bayamus – and his system of so-called ‘internal vertical justification’, or I.V.J, a method of making full use of both the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the printed page to respond to the content.

The Themersons were not generally inclined to dwell on the past, a reluctance also reflected in Stefan’s theory of history – ‘to know the direction of a movement, we must of course have history. But we need not as much of it as possible, but as little as possible.’ He once said that bibliography was his biography. In March 1967, Oswell Blakeston, a Gaberbocchus author, wrote, ‘Obviously a monograph could be written on all the fifty odd Gaberbocchus books.’ Of course, it would not be feasible to write a ‘biography’ of every title in the Gaberbocchus catalogue, and this is why we have chosen to concentrate on our selection from the most defining and visually striking books, paying particular attention to the engagement of form with content.In the words of the Dutch writer Doeschka Meijsing, what the Themersons did with their Gaberbocchus Press ‘was not designing, that word should be abolished here!’ The design of their books is testimony to something else – namely, ‘an understanding of the power of the written word.’

GABERBOCCHUS PRESS (1948–1979) and the THEMERSONS on paper, on screen, on stage

06.11.2019 — 06.03.2020

Opening: 05.11.2019 from 6 p.m.

Catapult

Project space ‘Kades-Kaden’

Rubenslei 10

2018 Antwerp

Hours: Monday–Friday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., weekends and holidays by appointment only

Entrance: Free

Exhibition curators: Catapult & Piet Gerards

Scenography: Catapult & Piet Gerards

Text: Jasia Reichardt, Walter van der Star

Photography books: Peter Cox, Catapult

Picture editing: Catapult

Exhibition In collaboration with Piet Gerards, Themerson Estate and GV Art london.

Text

and images with permission of Huis Clos (publication Biography of a

Publishing House. Stefan & Franciszka Themerson & Gaberbocchus,

Rimburg/Amsterdam 2017).

With the support of Graphius Group, Arctic Paper, Integrated 2019.

With

special thanks to Jasia Reichardt (Themerson Estate), Piet Gerards,

Robert Devcic (GV Art London), Walter van der Star, An De Coster (Arctic

Paper), Bruno Temmerman & Denis Geers (Graphius Group), Hugo

Puttaert (Integrated 2019)